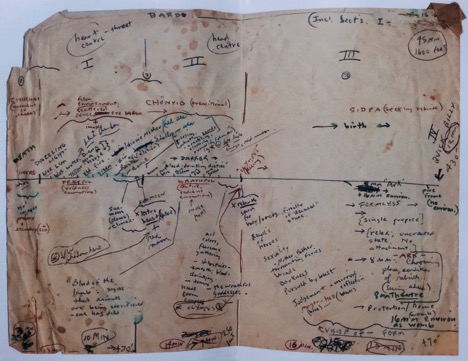

Bruce Baillie’s notes for Quick Billy, from the booklet accompanying the DVD of the film (photo courtesy of R. Bruce Elder)

Quick Billy (1971) offered me lessons in autobiography. One way of experiencing Bruce Baillie’s masterpiece is as an example of a type of art that has attracted attention over the past few years: The Buddhist American work. Artists from San Francisco have been especially prominent in this movement. When experienced as a piece of Buddhist art based on TheTibetan Book of the Dead (1927), Quick Billy appears to be a tragedy, a recounting of Baillie’s failure, when near death, to be released from the wheel of life and death: His concupiscence (conveyed in the close-up of masturbation and in the wondrous image of making love to Charlotte) and grasping at things (see the loving images of the critters around him and the beauty of the surroundings of his Fort Bragg cabin, which are lures for feelings and attachments) result in his being reborn (suggested when his parents come to visit their ill son). Sure, the reborn Baillie, the cowboy hero Quick Billy, appears to be vital, strong, and lusty. But, sadly, he is in the grip of illusion, bound onto the ever-revolving wheel of life and death, on a quest that might never end because of the mind’s tendency to fall prey to illusion.

There is another, complementary response that is possible, however, one that exists in tension with the Buddhist reading. This way of taking the film is to experience it as a piece of gnostic solar mysticism. Quick Billy can be taken as a story of Baillie’s falling ill, becoming delirious, and experiencing memories of his earlier self, his transformation and rebirth, through the power of the sun, as a vigorous, even myth-worthy individual. On that topic of coming alive again, the title of the film itself contains a rarely noted allusion to that phenomenon: Certainly “quick” is used in the title as a conventional epithet, commonly employed to refer to a cowboy’s being quick on the draw. But it is also used in the sense it has in the Christian creedal expression “the quick and the dead” (the living and the dead), which is usually associated with the Christ’s rebirth and ascension. So the title conveys the idea of “Living Baillie” or “Baillie Alive!” It is hard not to take such a meaning as celebratory.

Like Ezra Pound’s Cantos (1948), then, Quick Billy concerns going into the underworld, experiencing terror, undergoing transformation, and being reborn into light. Even the film’s erotic images, which on the Buddhist reading are taken as images of concupiscence, on this reading can be taken as implying efforts to merge with the sacred feminine—to effect a gnostic coincidentia oppositorum.

In Baillie’s film, each reel is distinctive. Each presents a different form of the Self. Reel One starts with a diffused Self about to dissolve into the light, and across its fifteen minutes depicts the beginning process of its assuming boundaries. Reel Two depicts the Self becoming an autonomous entity—or rather, falling prey to the illusion of being a separate existent. This false belief in all beings’ separateness is the source conflict of being fighting being. Reel Three depicts the Self’s involvement with the social world/image world, as further fictions of the Self arise. Reel Four concerns the false Self and myth.

Furthermore, Baillie identifies all forms of the Self with the cinema. Quick Billy’s first two reels present a first-person cinema (offering a document of a delirious consciousness becoming adapted to the actual world), Reel Three offers a second-person cinema (with Baillie looking at a family album and observing pictures of himself as though they were of another with whom he has an intimate relation), and Reel Four offers a third-person narrative. Through this taxonomic organization, Baillie suggests that cinema evolved out of consciousness and over time assumed forms increasingly distant from the deep Self. In presenting these cinematic modes in reverse chronology, Baillie suggests that the cinema’s original and true nature is as a document of consciousness.

Bruce Baillie presenting Quick Billy in March 1972 (photo taken by Kathryn Elder)

R. Bruce Elder