(Toni D’Angela). When and how have you started to love cinema?

(Monte Hellman). My parents started taking me to movies when I was five. They also took me to the theatre, including magic shows. I don’t remember when I started to differentiate between them. I remember the thrill of the curtain going up – the anticipation of magic.

Then a few years later I started going to the movies every Saturday afternoon. I particularly loved Tarzan, as well as all the serials: The Lone Ranger, Buck Rogers in the 21St Century are the first that come to mind. Coincidentally, I was given a camera and started taking pictures. Then I began photographing the children I baby-sitted. Then I built an enlarger out of a cigar box, a tomato soup can, a sheet of opal glass and my father’s old bellows camera. I also started writing and directing short plays.

I began going to the cinema as a place to dream. Ironically, I typically went to the movies during the day (weekends and holidays) and a club to hear Kid Ory play jazz at night. I guess the laws were more lenient then. Today a fifteen-year-old wouldn’t be allowed in a bar.

(Toni). Is there a specific reason why so many important filmmakers (Coppola, Bogdanovich, Scorsese, Cameron, Dante, Demme …) have begun with Roger Corman? Or maybe is it because he was always working with few money, so he was searching for young collaborators, young filmmakers?

(Monte). I think you’ve answered your own question. Roger was the only game in town.

(Toni). Which was your contribution to The Terror?

(Monte). I think it’s outlined very well in Brad Stevens’ book. Mainly, anything that wasn’t shot in the castle set, with the exception of a few scenes from Coppola. The sequence I had the most fun with was the hawk clawing out Jonathan Haze’s eyes, causing him to fall off the cliff. Jack Hill was my screenwriter.

(Toni). Godard, if I remember correctly, once spoke of you and Jack Nicholson on a mission at Cannes Festival to promote one of your western, in the 1960s, what do you remember about that?

(Monte) I remember it very well, mainly because I wasn’t there. Jack and I were partners. Since I was the only one with a job (as an assistant film editor,) Jack was elected to carry both westerns (in cardboard boxes since they weighed less than cans,) one in each hand (much like Willy Loman) to Cannes. I financed the trip. Because he was Jack (not yet a movie star, but still with enormous magnetism) he met everyone, and managed to get everyone to come to the screening he set up. Godard spoke of it years later in an interview in the New York Times.

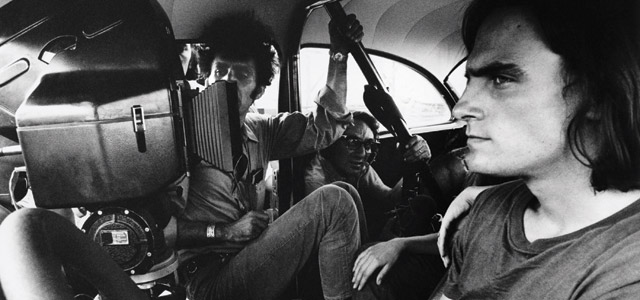

(Toni). In your westerns, you do not seem concerned about the myth of the border. In Two–Lane Blacktop (1971), in that frosty coast to coast without romance, the great american landscapes disappear, in a transaction which, it seems to me, refers to Minimalism, because the object you use, James Taylor’s Chevro resembles the counter of light of artist Bob Morris; the object has lost its effectiveness, its utility. Was it a metaphor meaning that the border, the myth of the American dream and the myth of the coast to coast (the journey on the road), has lost the ability to arouse dreams, emotions and movement?

(Monte). You’re speaking a language that’s completely foreign to me. I’m always fascinated by art criticism (as opposed to American-style movie “reviews,” in which the so-called critic frequently doesn’t even know what the various collaborators do) in spite of, or perhaps because of, the fact it has nothing to do with the process I go through. My creative process is intentionally an unconscious one. I try to shut off my mind in order to access my creativity. I encourage my collaborators to do the same. In another era we would have called it left brain vs right brain. I actually don’t know what the myth of the border or the counter of light are.

For me Two-Lane Blactop was the story of a man who suffered because of an inability to communicate his feelings. It’s an homage to Shot the Piano Player, and also, perhaps in some ways, The Asphalt Jungle. Road to Nowhere is almost the same story. I think most picture makers have only one story they tell over and over again.

This is not meant in any way to invalidate other interpretations. The audience is, after all, the final collaborator.

(Toni). The ending of Two-Lane Blacktop reminds me of Le départ by Skolimowki, freeze-frame burning dreams, intensity, bodies, minds…

(Monte). I didn’t meet Jerzy until 1973, and the first movie of his I saw was Deep End. I never saw Le départ, so can’t comment.

(Nicole Brenez). You said once that only an anonymous German spectator, during a Festival, had understand the true meaning of the end of Two–Lane Blacktop. Please tell us what he said !

(Monte). It wasn’t the ending he talked about. Most of the critics at the time talked about the social and philosophical aspects of the movie. All my brewery worker saw was the human story, the love story.

(Toni). Do you think that the America of today is better than that of the 1960s or perhaps it’s lacking sense of collective participation, joint actions, culture, etc.?

(Monte). Contrary to popular belief I’m in many ways a reactionary. When I was a child my elders frequently commented that I should have been born in the 19th century. But I’m in conflict. I’m an early adopter of new technology, while at the same time feeling a nostalgia for the old. James Taylor, as he’s preparing for his last race, is moved by the sight of horses off in the distance. I love the digital world, and don’t intend to return to the world of film. But I just bought another specially designed CRT monitor, a monstrosity I don’t really have room for, because it was and still is the best way to evaluate gradations of color and grey when processing still photographs.

To be more specific with regard to your question, I have the illusion that the America of the 1960s was more cohesive, and that human interaction was at the very least more tactile. I’ve always been somewhat of a hermit, so in many ways having “friends” on Facebook is the closest I’ve come to having contact with a wide circle. But in the 1960s I still hung out in coffee houses, and could at least hear and smell, if not touch, large groups of people. Today the coffee houses are gone, and people in public no longer talk – they merely communicate by texting, even if the person they’re texting is only across the room.

(Toni). Difficult question: what does the Western is? The highest narration of the birth of the american country? The epic of courage of becoming new men? A non-authentic representation of American history? The American genre par excellence? Or all these things together?

(Monte). We’re looking at the Western today through very different eyes than the ones perceiving it when it was born. Edwin S. Porter was the father of the Western, and in his day it must have been like making a space travel movie today. Even in the 1930s, the era of The Virginian and Stagecoach, the time of the old West was much like our making a movie today about the 1980s.

That being said, for me the Western was the closest we could get to Greek tragedy. It allowed for big dramas and big emotions on a giant stage. It was separated from the world of kitchen sink dramas, and enabled us to deal with man’s relationship with man, god and the universe all at the same time.

(Toni). In your westerns you introduce sudden cuts, slow motions, the situations are suspended, the characters psychology is undetermined, vague, enigmatic, your movies are full of silence and expectations, and also the landscapes are unattractive, your heroes (Jack Nicholson, Warren Oates, Fabio Testi) are gunfighers without gun and with a broken hand, workers that break their backs but keep on dreaming, gunmen without compass. A brave operation, a new style, combining Ford and Bergman! The question is: have you been inspired by anything or anyone to do these innovations? Antonioni? Beckett?

(Monte). As I indicated above, I feel more like an imitator than an innovator. My westerns were inspired by all the westerns I’d grown up with. It’s always hard to determine what one’s unconscious influences are. Of course I’d been exposed to Bergman and Antonioni. I’d been deeply engaged with Beckett. But my collaborators were perhaps my strongest influence. Carol Eastman’s script for The Shooting contained many explicit descriptions. She wrote in a very visual way. And Jack Nicholson’s script for Ride in the Whirlwind incorporated many descriptions from the diaries upon which it was based. All of which was digested and regurgitated by way of my unconscious.

(Toni). How did the audience and the critics in welcome your movies?

(Monte). My westerns were introduced to the world in France. The Shooting played for more than a year, and Ride in the Whirlwind for six months. I became a celebrity in a way for which I wasn’t prepared. The critics were almost embarrassingly effusive. I was trying to book passage on the S.S. United States for my family and my dog. There were only 12 spaces for dogs, and they were already booked. But the manager of the steam ship line recognized my name as the author of “THE WESTERNS!,” and he made extraordinary efforts to find our Beardie pup a berth. And then there was the fan whose shopping cart followed mine around a Paris super market until he succeeded in getting my autograph. Fortunately as the years passed, I managed to slip back into a life of comparative anonymity.

(Toni). In the wilderness of Ford, Walsh or Wellman, something happens that produces rebirth, novelty, change. Your deserts are really empty, but you want it like that, there’s hope. But I think that yours isn’t simply a cruel parody (such as in Robert Altman, for example), because you are sincere and profound, and then you love the western, or I am wrong?

(Monte). I do love the western. I admire McCabe & Mrs. Miller, but I know what you mean by parody. I hope I’m not guilty of it. I felt that marred Nashville.

(Toni). Yes, I admire it as well… And what about your professional adventure in Italy (and Spain)?

(Monte). China 9 was one of the most joyous experiences of my career, and Iguana one of the most miserable. On China 9 the camera crew cooked pasta every night, and everyone told jokes that got incorporated into the script the next day. Not to disparage the wonderful script by Jerry Harvey and Doug Venturelli, but we literally transformed and augmented it as we went along. We started without knowing what the ending would be, and it slowly revealed itself to us just in time.

Iguana suffered from a producer who was the reincarnation of the Mark Lawrence character in The Asphalt Jungle. He’d sweat every time he had to handle money. Because he was paranoid about paying for anything in advance, we’d literally wait all day for a necessary prop necessary to begin shooting. The production went needlessly over schedule and budget because of this.

But I fell in love with both Italy and Spain. The scenes at the Hotel Scalinata di Spagna, church of San Pietro in Vincoli and Sant’ Eustachio coffee bar in Road to Nowhere express some of that love and nostalgia.

(Toni). The US edition of your italian western, China9, Liberty37, with Fabio Testi and Warren Oates, was cut, especially the sex scenes with the botticelliana Jenny Agutter: american puritanism? I also think the soundtrack of Pino Donaggio in American Edition is more “country”…

(Monte). Only the TV version was cut in the U.S. There was never a theatrical version, but the video was widescreen and uncut. However the Italian version was extensively cut for various reasons, not the least of which was superstition about circuses and the color purple, as well as a lack of comprehension of some of the humor. As far as I know, there were never alterations to Pino’s sound track.

There’s currently no DVD version in the U.S. Warners, who own the rights, have done a beautiful restoration of the picture, and are selling the rights around the world. However they’ve botched the sound, inexplicably adding the Music and Efex tracks over the original sound, effectively doubling the volume, which all but drowns out the dialogue. It would be easy to fix, but so far they’ve been unwilling to do it.

(Toni). What do you think when Quentin Tarantino in Italy declares that Sergio Leone and other directors of spaghetti-western are more good or interesting than any American directors, even Ford? Is it nonsense? A provocation? (I’d like to remember that once Welles said that his three favorite filmmakers were: Ford, Ford, Ford). How do you rate Sergio Leone?

(Monte). Sergio was a dear friend, so I hope he won’t object to my saying I admire some of his movies more than others. I think Once Upon a Time in America is wonderful. Once Upon a Time in the West and Duck You Sucker are nearly as good. I have a hard time with some of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

As for Quentin, yes he can be a provocateur. To paraphrase Will Rogers, I don’t think he’s ever seen a movie he didn’t like.

(Toni). Your latest film, Road to Nowhere, is one of the most beautiful of the last ten years, and one of the most shocking, recalls me a little Lynch and Godard, Bob Morris and Raymond Carver. I would like to know how the idea was born and how you judge it in relation to your career, the prize won in Venice and the judgments of the critics?

(Monte). I have only a limited knowledge of Lynch: Elephant Man, which I liked; Dune, which I tolerated; and Blue Velvet and Wild at Heart, both of which made me angry. The only thing I remember about Mulholland Drivee was that it was obviously incomplete, with loose ends that never got tied or even shot. And that Naomi Watts seemed better in the scene from the movie within the movie than as the “real” person. By the way, I thought she was excellent in the new Woody Allen, which I love in every other way as well.

I admire Godard as an artist and as a human being, but see little connection between his work and mine. Much the same way I admire Brecht in the theatre, but chose to go in quite a different direction myself. I don’t know Bob Morris, and only know Raymond Carver as seen through Altman’s eyes.

Steve Gaydos, a long-time collaborator, had the idea for Road to Nowhere, and was encouraged to write the script because of my enthusiasm for the idea. He claims it’s the first of his ideas I’ve responded to in 40 years.

I know it may sound extravagant, but I feel Road to Nowhere is my first movie. I feel the others were merely rehearsals. Part of this is that the others were all works for hire, and this was the only of my own projects I’ve so far been able to realize. Of course they’re all my children, and I love them, but Road to Nowhere seems to be the first legitimate child born out of a loving relationship.

And I’ve become a better father. I learned that the child had a right to its own unique life, not just a shadow of mine or a projection of my unfulfilled dreams. I gave the child the chance to become what it wanted to be, as an individual entity, and I listened to what it told me. It became something quite different from what I imagined it would be, and I wasn’t upset but glad. I’m proud of it, not as my offspring, but as a unique creation with genes from a great team of collaborators.

The response of the critics in Italy has been overwhelmingly positive, even passionate. Since we premiered in Venice it’s not surprising that a majority of press were Italian. The volume of reviews from other countries has been smaller, and varied from country to country. Mostly positive in Spain, Portugal, France and Argentina. Mixed in the Northern countries, Austria, Germany, the UK. Especially in the UK some of the critics seemed angered by the way the movie challenged them, just the opposite of the way the Latin language critics embraced it. The test will come when we open in Paris early in 2011.

Winning a golden lion in Venice, even a “separate but equal” one, was one of the great thrills of my life. To quote GTO in Two-Lane Blacktop, those satisfactions are permanent.

(Toni). If I think to Vertigo, for your Road to Nowhere, I’m wrong?

(Monte). If you think Vertigo, you are absolutely right.

(Nicole). Since your so deserved Award in Venice, Italy, is the professional situation better for you in the USA?

(Monte). I have no idea. I’m so far out of the system, it doesn’t seem relevant. The greatest decision I ever made, or my daughter Melissa made for me, was to take control of my (our) own lives, and produce our own movies. I don’t see myself turning back from that freedom.

(Toni). Are you going to shoot any movie soon?

(Monte). I have two new projects, another script by Steve Gaydos, and another of mine that got put on a back burner when we started making Road to Nohwere. We hope to get one or the other on the boards before the end of 2011.

(Toni). You often have realized film on commission. Today you made a film that disturbs the voyeur, passive, indolent, eating popcorn viewer : is it an angry revenge? Basically, this is a film that never ends, even when the money for shooting ends, the film continues to interrogate the viewer, to put it into an inner conflict, to push it to make questions to himself. And this is its great strength.

(Monte). I don’t eat popcorn anymore, since corn is now mostly genetically modified. But I’m happy if the viewer, with or without popcorn, is disturbed. Theatres with viewers, iphone in hand, texting each other and the outside world, have become gigantic living rooms. Instead of the hot medium that Marshall McLuhan admired, movies too often have become a giant clone of the Medium Cool of TV.

My intent was to demand the attention of the viewer. If he or she doesn’t have the desire or attention span to give me that attention, my first reaction was to tell them to stay at home. However, I’ve been advised that this is too rash, especially if it interferes with our ability to recoup the cost of the production. So instead, we’re now going to advertise at the box office: Wi-fi available inside.

(Nicole). You were one of the first, if one the first one, to use the Canon 5D Mark IIs, for Road to Nowhere. Will you experiment new tools for your shootings? What do you think about the new cameras?

(Monte). I was an early adopter of digital still photography, particularly digital print making. I love the control it gives you. Even though I miss the old upright moviolas, and the particular influence they had on the way a picture was edited, I’ve found the post production on Road to Nowhere the most satisfying I’ve ever experienced. And for the first time I used an editor other than myself, the enormously talented Celine Ameslon. I expect our collaboration to continue for all my future movies.

Digital camera technology is changing by the day. The thing that makes the Canon unique in cinema is the size of the sensor – 2-1/2 times bigger than 35mm movie film. Even though there are still problems with the rolling shutter, and other cameras have solved it, my DP Josep Civit and I will still probably stick with the Canon or its equivalent on the next movie.

(Toni). In Road to Nowhere there are fragments of El espiritu de la colmena by Victor Erice, where a girl accepts and embraces a “Monster” (the diversity, the otherness) – thanks to the suggestion of James Whale’s film. In your first film, Beast From Haunted Cave, there was a monster that stops the conspiracy and intrigue of unscrupulous characters, and on the other hand, after being disturbed and harassed, he is killed by the heroes of the film.

(Monte). For some time I’ve been intrigued by the idea of the monster, the myth of “Beauty and the Beast”. It was my inspiration in making both Iguana and Better Watch Out. I was inspired by the musical The Phantom of the Opera. I think these conflicts are buried deep within us all. We’re able to defuse them, to release some of our fears, when we go to the movies.

(Toni). Tom Russell is tha author of the wonderful soundtrack: can you tell me why you choose him? Are you an admirer of his since a long time?

(Monte). I discovered Tom several years before making Road to Nowhere. I was searching for a way to utilize his music in a movie, and happily I found it.

(Toni). In both Cockfighter and Iguana, characters refuse or escape from human Consortium, close in silence but strive; in the final of Iguana, the protagonist is immersed in water, in death, to escape to the capture of men that wouldn’t give him the opportunity to live in freedom… The isolated man, struggling against the other, to assert its diversity, its independence: is it a situation that interests you?

(Monte). I think all heroes are alone, fighting for whatever it is that’s important to them. We go to the movies to identify with these heroes. We all strive to become the heroes of our own lives. The hero who is driven to isolation or silence is someone I can particularly identify with.

(Toni). Also Road to Nowhere seems a eulogy to the autonomy, the courage to experiment, against every rule… even that of winking to the Viewer. The film of an independent artist.

(Monte). I didn’t intend to break all the rules I’d been taught to observe. But when the script demanded it, I found myself fascinated by the resilience of the audience. We constantly tell the audience “it’s only a movie.” We shock them out of their willing suspension of disbelief. And it takes them only seconds to begin to believe again. It was a great discovery for me.

(Toni). Let’s go back to Iguana, was Warren Oates supposed to be the protagonist? I think Warren Oates was a great actor. Intense. Able to touch the keys of intimacyt and explode like a flame. People say incredible stories about him and Peckinpah.

(Monte). Of course Warren would have been wonderful in Iguana. But he died five years before, so I don’t remember even regretting he wasn’t available. He and Sam didn’t have any scenes together in China 9, but they were quite a pair off the set.

(Toni). We know that you was the ghost editor for some directors, even Peckinpah, but I would like to ask you which part you got in editing Apocalypse Now? I guess you met Coppola in Corman’s Factory.

(Monte). Yes, I knew Francis from the Corman days. He asked me to look at Apocalypse Now at several stages of the editing, and he asked my opinion. But I wasn’t involved in any of the editing process.

(Toni). PatGarrett & BillytheKid, once I’ve read that you would have had to do it yourself, right?

(Monte). I was hired to direct Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, and I worked with Rudy Wurlitzer on developing the screenplay. The picture was put into turn around at MGM, and a new administration revived it several years later with Peckinpah.

(Toni). What can you tell us about the Hammer production of Shatter? The character (always in conflict) of the film has strokes of some of your heroes, but the movie is not entirely yours …

(Monte). I had a fight with the producer over an artistic decision, and was replaced half-way through the production.

(Toni). What is your relationship with the script? Doyou change it during the filming?

(Monte). I didn’t change a word of The Shooting, except to cut out the first 10 pages before starting, and the usual amount of material during the editing. China 9 and Roadto Nowhere were constantly being created or recreated on the set.

(Toni). Regarding the relationship between director and screenwriter. In Road to Nowhwere the director does not listen to the “good” advices of the writer. And the writer appears to be a “balanced” person…).

(Monte). The writer is “balanced”, the director isn’t.

(Toni). Which are the directors that more have influenced you, both as man and as an artist?

(Monte). As an artist, I think my greatest influences have been John Huston, Carol Reed and, to a lesser extent, George Stevens. As a man, far and away the one I admired most was Jean Renoir. I only hope he had an influence on me in that regard.

(Toni). Interesting, Stevens! Critics speak very little about him. Why do you think?

(Monte). Perhaps because his movies had no easily recognizable persona, or because some of them have become dated by primitive technologies like the make-up in Giant. He was a great interpretive artist, much like Toscanini or one of my other heroes, Carol Reed. But I mentioned him as an influence because of one movie, A Place in the Sun. It may be hard to imagine now, but at the time the movie had an extraordinary impact. Chaplin called it the greatest movie ever made. It’s influence was equal to the effect L’avventura had on an unsuspecting filmmaking world. Like it or not, you couldn’t help being affected by it. I consciously paid homage to A Place in the Sun in Cockfighter, through the use of extremely long dissolves.

(Toni). The French critic Serge Daney said that in the films of John Huston is a mythology of failure: are you interested in this?

(Monte). This kind of criticism is entertaining to read, but I feel has no relation to the creative process, Huston’s nor mine. I feel Huston was an explorer, exploding with curiosity and adventure, with a great sense of humor as well as cruelty.

(Toni). According to Truffaut, Renoir filmed actors and personalities, not ideas and situations, work on the actors, is the “midwife”, he gives birth to the “child” (the belief) that is in the actor. Is it a method that convinces you?

(Monte) I’m always pleased when those I admire turn out to have discovered the same methods I use.

(Nicole). In the cinema and in the literature of today, is there works that you like?

(Monte). There’s so much literature from the past that I haven’t got to, I rarely read literature of today. But I do see contemporary cinema. And I’m constantly making new discoveries. Tsai Ming-Liang, Fatih Akin, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Arnaud Desplechin, Paul Thomas Anderson, Matt Porterfield, in addition to my long-time friends Rick Linklater and Wes Anderson. This is in no way a complete list.

(Toni). You were interviewed by Wim Wenders in Chambre666, did you get to talk about the sense of cinema (and life) with other directors among those interviewed by Wenders?

(Monte). I’ve never seen the movie, so don’t know what others had to say on these subjects, and don’t remember what I had to say. I’m sure I had drinks on the Carlton Terrace with many of the interviewees, but don’t recall any conversations more serious than who had the best looking breasts on the plage.

(Nicole). How do you imagine the future of cinema?

(Monte). I think that’s the same question Wim Wenders asked. I think technologies will constantly change, but I don’t see it affecting cinema itself. Audiences will become increasingly detached from the experience, but mostly because of the lack of serious demands on their attention. But I think the need to be touched, to experience the purgation of pity and fear, will remain a constant. It will be our challenge as picture makers to meet this need.

(Toni). And of your work as university professor what can you tell us? What do students think of cinema and what are the difference from young people who wanted to do cinema in the 1960s?

(Monte). I was in that group of young people in the 1960s, and I remember we were very serious. And we didn’t have any idea as to what a “career” was. There are young people today who are equally serious, and there are others whose only thought is how to break into the system. If anything they’re over-educated. They pay too much attention to their teachers, myself included. I have mixed thoughts as to the value of cinema studies, as opposed to letting the camera be your only teacher.

(Nicole). What did you think of Cinema today? Do you still Believe that cinema, such Whale’s movie, has the power to provoke thought, strength, courage?

(Monte). Cinema is many things, from the pointless sequels and re-makes to the experiments of today’s new generation fresh out of film schools. Being an optimist, I believe there will always be cinema that provokes – at the very least, thought, strength and courage.

(Nicole). What would be your advices for young filmmakers?

(Monte). Don’t try to do what others say you should do. Don’t try to predict what will be successful. That’s a fool’s game. Do what your heart tells you to do. That way, there’s no such thing as success or failure, because you will have made a movie you wanted to make. If you try to be a success, and you fail, you’ll have nothing

(Nicole). Where are the prints of your films? Do you know how they will be preserved?

(Monte). I have the negatives, interpositives and prints of The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind. I also have prints of some of the others, but most of the color prints are faded. I don’t control the negative materials. I see most of my movies being preserved only as digital materials.

(Toni). What about the difference between digital image and film?

(Monte) Toni here is no one answer, since the technology is changing fast, and there is not just one digital image. Generally speaking, film still has more latitude, but the difference keeps getting smaller and smaller. And digital will soon equal or surpass film.

The camera I used has a sensor that’s larger than 35mm movie film, being the size of 35mm still film. The image therefore has a shallower depth of field than movie film, again being the depth of field of still film. But it still creates unfortunate digital artifacts because of the rolling shutter and inability to create raw uncompressed images, as it can in still mode. But other digital cameras have solved this problem. So at this point, I still like my camera best, but will like it or a successor better when it retains the large sensor, but can shoot uncompressed with no artifacts.

(Nicole) What do you thing about the books written about your works, as Charles Tatum and Brad Steven’s works?

(Monte). I don’t understand French well enough to say I’ve read Charles Tatum’s book, nor have I actually read Brad Steven’s book, although I spent a long time emailing him my answers to his questions. I feel they’re both interesting discussions on the undiscussable, with Brad’s going into the greatest detail.

(Toni). I remember a picture of yourself in company with John Ford. Where and when? How did you meet Ford?

(Monte). We met at the Montreal Film Festival in 1966. His silent movie Straight Shooting was playing, as well as my picture The Shooting. A year later in Montreal I was on a jury headed by Jean Renoir.

(Toni). It seems that your meeting with Ford was not interesting…

(Monte). Of course it was interesting to me. But he wasn’t very friendly or communicative. Or maybe he just didn’t open up easily to strangers. Or maybe I didn’t.

I also met Lang, who seemed at first equally surly, but actually wasn’t. He was charmed by barely 4-years-old Melissa. I have a picture of him with her.

But both Ford and Lang put on a stoic persona for the world to see.

(Nicole). I just wish to say: Monte Hellman, without you, the American cinema would lack the sense of ethics, deep beauty and amour fou!

(Monte). I accept that as a compliment of the highest magnitude.

Edited by Nicole Brenez & Toni D’Angela