A Cinephilic Confluence

Cinema has exerted a very strong attraction on filmmakers and film viewers and has survived all vicissitudes, even its own death, ascertained by several critical voices in the 1980s, among them Susan Sontag (1996). In the post-cinematic age, the love of moving images has not only survived, but actually expanded to a myriad of new consumption sites and/or platforms, allowing the experience of cinema to grow in nature as well as in scope. I venture that cinema’s survival is due to the fact that “movies” are more than an industry, an entertainment or an art form. There appears to be a socio-psychological dimension in this enterprise which binds filmmakers to their works, on the one hand, and film viewers to screens or images, on the other—that actually binds filmmakers to film viewers, and transforms the latter into the former.

Analyzing the affective dimension of cinephilia is a problematic endeavor because of the subjective quality of love. For the moment, I propose to delve merely on the urge of expression as it is made manifest through films that explicitly address this urge. Compulsive film-watching often leads to productive careers in filmmaking. That was the case of the community of young film critics of the Cahiers du cinéma in the 1950s Paris, in France; it was also the case, decades later, for Quentin Tarantino, who rose from clerk in a film rental shop to the frontline of an indie crossover generation. It is around this assumed cinephilia that the metacinema-engendering reflexivity takes place (Habib 2005).[1] For these filmmakers, metacinema is the corollary of a personal search surrounding their passion; for the likewise obsessive film-viewers, metacinema is a way to penetrate a universe that is a perpetual source of desire. For both, cinema is a self-search, an apprenticeship, a philosophical reflection. For instance, in an interview given to Gene Youngblood in 1968, Jean-Luc Godard states: “Before I was feeling it; it was very unconscious. Now I want to be aware of it. I want to know what this passion is made of” (quoted in Sterritt 48). Jean-Paul Tőrők (1978) claims that all great filmmakers contributed to the inventory of films about cinema (26). Frédéric Sojcher (2004) goes further when he states that each film director always ends up questioning him- or herself about cinema, in one way or another, at a given moment in his or her directorial career, either directly or indirectly. The present article follows this rationale by focusing on metacinema as authorial discourse. My argument is grounded in a revivification of the author who both Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault, in the 1960s, proclaimed dead.

Barthes (1967) meant to counteract the tendency to trace any and all meanings present in a given literary work back to its physical author. He wanted to denounce “the message of the Author-God” (4) and recognize that a text had multiple interpretations that depended on its readership. By arguing in favor of a new authorial and abstract entity—the scriptor—Barthes intended to empower the reader and encourage interpretation. Through the symbolic death of the author, he sought to neutralize authorial intention. Like-minded Foucault (1969) confirmed that writing was a creative act and not the representation of a biographical expression. Yet in order to avoid discarding the author altogether, he proposed the concept of “authorial function.” This allowed him to justify the homogeneity and specificity of a certain body of work (oeuvre) via the biological existence of the author without having to accept the chronological information pertaining to that person and his or her semantic intention. Thus, an inversion of the traditional critical process occurred, one in which the creator was interpreted according to his oeuvreand validated externally by society in a given historical context.

François Jost (2001) resurrected the cinematic author as a deliberate marketer(le vendeur), who is both located in the text and in the epitext. According to him, the author self-promotes him- or herself, contributing to his or her own exegesis. The interviews given to the media convey information about the author and his or her intention(s), but especially a differentsort of information, thereby changing the perception that the audience has of the artist, who becomes a brand. All of the director’s films are the object of an “authorialization” (auteurisation) because they are prone to an affectionate and cinephilic appreciation prior to their viewing. Yet the most important inference to be drawn from this resurrection is that the author produces discourse as a real-life person—she or he is disseminated both through biographical and textual manifestations. However, the factual information pertaining to a biological existence should only be considered here in terms of an emergent set of artistic concerns. It is not irrelevant that a certain director opts for a recurrent theme and chooses certain enunciative procedures.[2] In fact, what attracts some directors to the essence of their art constitutes a fundamental element of the meta-cinematic equation.[3]

Emphasizing Enunciation as Authorial Discourse

Enunciation (l’énonciation) is a term from the field of linguistics used by Émile Benveniste in “L’Appareil formel de l’énonciation” (1970). As the process of articulating words and sentences, it cannot be separated from the resultant text as a whole (l’énoncé). When understood in a broad sense, this dichotomy is articulated around a process of “textual” expression and itsproductof expression can be applied to cinema. But who or what enunciates?

David Bordwell (1985) suggests that a film narrates itself. Bordwell’s impersonal enunciation, just like the one advocated by Christian Metz (1991) in his later years, is specifically cinematic. Nevertheless, a truly impersonal film, enunciated by itself, would exist ab nihilo. According to Bordwell, the act of enunciating a narrative per se—or narration as he calls it—is a matter of emplotment: the constitution of a chain containing all narrative actions as they are conveyed in possibly nonlinear order. From this, film viewers have to gather the linear occurrence of the facts, which taken together form the story (Bordwell 51): “Narration is better understood as the organization of a set of cues for the construction of a story” (62). For Bordwell, then, fictional narration requires the dramaturgical organization of the plot through the technical composition of materials. The narrative and technical/aesthetic choices made before the film is finalized, and thought to exist in and by itself, require authorial decisions. Thus, since plot mechanics is, in fact, a very subjective operation, no actual neutrality is valid in film, although this is masked under the cloak of transparency. It is this transparency that Bordwell has in mind when he suggests that a film narrates itself (i.e., impersonal enunciation). The film, in itself, is made to look impersonal, but is made by people; all film materials emanate from the authorial source.

Against Bordwell and Metz’s view, André Gaudreault (1988) posits that a film possesses two layers of “narrativity:” “showing” (monstration), which is profoundly visual and related with the juxtaposition of film frames; and “narration” (narration), a superior form anchored in filmic time and having to do with the relationship between shots (55). The source of this narrativity is what Gaudreault calls the “mega-enunciator,” an abstract function since the author remains unknown to viewers in real life.

Going forward, I will refer to “enunciation” as the act through which the enunciator manifests his or her choices under the form of specific film techniques. As an extension of that, I propose that the concept of “authorial enunciation” should be used to refer to all the technical and aesthetic work undertaken by the film director, regardless of its more or less concrete nature and the way it is conveyed: (1) by the director in first person (be it in his or her real-life identity or through a more abstract implied author); (2) through diegetic characters; (3) or even through the apparently neutral point of view of the camera. I would argue that the most important thing is to see how the director’s intervention corroborates the self-reflexive contents of cinema as a subject. This means that enunciation also covers the concept of discourse, an elusive term which is sometimes blatantly confused with ideology.

Émile Benveniste’s concept of “discourse” (discours) as an act of language presupposes an intention on the part of the speaker to influence the listener—through the posing of questions and intimations, the use of certain verbal inflexions and words (such as “maybe,” “yes,” “no”), etc.[4] Benveniste’s discourse makes use of the potentiality that language holds. In other words, it is an act of individualization—a material choice endowed with a meaning (75-78). Filmmaking, likewise, draws from a well of artistic and technical resources,[5] and the film becomes a subjective expression. Bordwell (1985) claims that the technical composition of the film materials is very personal. According to him, the filmmaker’s decisions concerning the mise-en-scène, cinematography, editing, sound, [etc.] form the “style.” Taking this subjectivity as the starting point, I define “discourse” as a message that registers through the enunciation. All films enunciate, but some are more discursive than others because their authors make an effort to place enunciation openly at the service of what they have to say about their worldview and artistic philosophy (which I call “cinevision”). The more discursive a film is, the greater the tendency to be self-reflexive and flaunt the author’s intention. This is not to be confused with other forms of ideology, which, nevertheless, may be concurrent with a specific position on art.

Consequently, I argue that all works of metacinema are acts of enunciation that are also intrinsically discursive because the will to express something about cinema as a medium and an art form is common to all of them, regardless of their artistic validity. In this article, I consider metacinema to be endowed with a set of ideas not only connected to the authors’ worldview, but most importantly related to their cinevision. Partly following Gaudreault, I use the expression “chief-enunciator” to refer to the author, but endow the term with an additional layer of stylistic and thematic intention. As such, the chief-enunciator not only has the urge to enunciate, but has a very characteristic way of doing so.

Once More unto the Meta

The word “metacinema,” despite its recurrent use in cinematic postmodernity, is far from having an unequivocal meaning; its signification is entirely user-dependent. In fact, theoretical discrepancies are often so intense that the same expression can be used with diametrically opposed meanings.[6] Therefore, in this article I do not purport to apply an all-encompassing definition to the concept of metacinema, but only to express my own point of view on the subject.

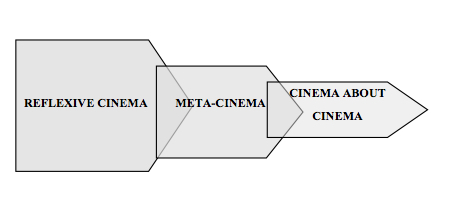

I argue that “metacinema” refers to all the films that express / expose themselves in two simultaneous ways: as enunciation (énonciation), therefore revealing the cinematic technique and film labor in general; and as the product of that enunciation (enoncé). Hence, metacinema is a filmic category that is doubly expressed/exposed, a fact that endows it with a higher artistic and documental (i.e., fact-conveying) richness than the one contained in all reflexive cinema and the subcategory of movies about movies. Metacinema is the middle category in a triad, superseding in versatility both of the categories it is usually paired with. A diagram helps to realize its relative importance and affinities.

Figure 1. The place of metacinema in the landscape of anti-illusionism.

Reflexive cinema exposes the intrinsic artificiality of all filmmaking and its products. Therefore, it includes both documentary practices and experimental cinema, the two opposite poles of cinema that are less inclined towards fiction. Documentary film usually implies a contact with reality, whose visibility and importance it enhances. An authorial point of view in the subject matter and in the formal manipulation of the materials can be considered a narrative, but it does not usually register as fiction.[7] Conversely, experimental cinema aims at a non-normative and all-expressive authorial subjectivity, but the film materials and the subject matter are endowed with a certain degree of abstraction, which tends to reduce an eventual story and its characters to a metaphorical stance. Documentary film is too realistic, experimental cinema is too artificial, and neither of them is specifically fictional.

Cinema about cinema in a restricted sense, on the other hand, describes the sort of films that merely depict the world of the film industry and their inhabitants, be it the commercial mainstream with its powerful main companies or the amateurish cinephilic drive of arthouse filmmakers. Although they are set in the film world and show filmmakers at work and/or viewers watching the films in diegetic movie theaters, these films are under no obligation to faithfully portray the making of cinema as it really happens in real-life situations. During Hollywood’s golden age, they actually avoided doing so because it was deemed bad for business. The Studio moguls dictated that Hollywood was a mystery that should never be disclosed to the laymen lest it reduced its public appeal, the so-called Myth of Hollywood (Anderson 1976; Ames 1997). Hence, this category is also known as Hollywood on Hollywood, despite the fact that the films it includes do not always depict the Hollywood industry, either geographically or culturally. Moreover, the depiction is usually restricted to the above-the-line roles in a film crew (stars, director, producer, screenwriters) and/or the film world may be only a background for a story of interpersonal relationships. Additionally, these films do not deal in covert portrayals of creatorship and spectatorship, which are nonetheless a fundamental part of what cinema is and how it works.

I claim that metacinema falls in between reflexive cinema on the one hand, and cinema about cinema on the other. It simultaneously reveals the cinematic technique, including the apparatus that enables it, and the underlying authorial discourse about cinema in general and/or a film in particular. Metacinema is both an aesthetic/poetic gesture, on a grammatical level, and a conceptual/ideological position, on a discursive and narrative one. At its best, metacinema is both figurative and fictional. Thus, I ague that what is specific about metacinema is the simultaneous fulfilling of the four following conditions: (1) metacinema must be an activity performed; (2) it involves an authorial discourse, conscious and deliberate; (3) it takes place throughout the entire film and manifests itself, directly or directly, in the subject and the story; (4) it results in a narrative film focusing on, in one way or another, on the essence of fictionality (and its relationship with artifice).[8] The first condition exposes the cinematic technique without which cinema could not exist strictu sensu; the second exposes the director’s point of view and transforms the film in a kind of essay about the nature of filmmaking; the third ensures that the film is, in fact, about the cinema and that such an environment is not a mere pretext for a facile spectatorial seduction; the fourth highlights the importance of the fictional impulse for the development of cinema as an activity and its artful and artificial nature.

I contend that films fall into a specific major category depending on the higher or lower incidence on one of the four above listed criteria. Consequently, the phenomenon of metacinema needs to be addressed on four fronts, which together form a taxonomy I developed with the purpose of helping to empirically dissolve the constant theoretical overlaps between concepts, and which I have analyzedin full elsewhere (Chinita 2008). This taxonomy consists of four main categories: (1) films about the film industry; (2) cinematic allegories; (3) hybrid films; (4) metanarrative. Category 1 evinces the literal meaning in the stories told and the professional universe portrayed; category 2 deals with the figurative meaning of the films and its cinematic underlying discourse; category 3 is a combination of literal and figurative meaning, to the point of blurring the lines between one and the other; category 4 concentrates on narrative and on the goal of drawing attention to the process of fictionalization involved in filmmaking. In this article, I will focus exclusively on the hybrid films, which is the more complex of all four categories.

This taxonomy of metacinema is organized primarily according to the films’ formal structure and its functionality; theme plays a secondary role in it. My categories are not hermetic, but I chose to allocate each film to a single category. Unlike other taxonomies, this empirical one is perpetually unfinished. As long metafilms are made, this taxonomy will, theoretically, remain a work in progress. For instance, prominent examples of metafilms in the last decade include The Artist (Michel Hazanavicius, 2011), Hail Caesar! (Coen Brothers, 2016), Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino, 2019), and Mank (David Fincher, 2020).

Self-Reflexivity as the Height of Metacinema

In 1979, Don Fredericksen observed that perhaps no definition of reflexivity is possible “which is not banal or reductive” (319). In 1987, Jacques Gesternkorn more or less confirmed this by providing the shortest definition of reflexivity known to me: “reflexivity appears first as a proteiform phenomenon of which the smallest common denominator is that it consists of cinema turning upon itself”[9] (7, my translation). He further added, however, that two types of temptation should be avoided: that of considering all films as self-revealing, and that of reducing reflexivity only to those films that are directly aboutthe cinema.

Of the many theoretical accounts of (self-)reflexivity and metacinema that exist, only a few touch upon the creator from an enunciative perspective. For example, Robert Stam in 2000, in an entry to Film Theory: An Introduction, revised his previous taxonomy (1992), adding the category of authorship as the study of the creative phenomenon. Gloria Withalm, also in 2000, disclosed her very detailed taxonomy, which included a section for creatorship as well. Most notably, Nicholas Schmidt (2007) effects a categorization based on the dichotomy illusion/reality and the authorial expression of the film director. His taxonomy is comprised of (1) film-on-film, in the broad sense of an embedded fiction either in the form of a film projection of a film shooting; (2) mise en abyme, designating the presence of one work inside another of the same nature; (3) metafilm, as the portrayal of filmmaking but endowed with a critical discourse.

According to Francesco Casetti (1992), metafilms about the film industry reveal the different stages of existence of a diegetic metacinematic opus in a way that highlights the artistic and commercial options taken by all those characters involved in the process. On this view, films about the film industry are “an interesting laboratory to study the processes of [cinematic] enunciation” (376); these films have a dual dimension to them: on the one hand, they “make a mise-en-scène of [their] own existence;” on the other hand, they “represent [their] own nature as representation” (375). The narratologist Lucien Dällenbach (1977) observes that the diegetic mirroring that focuses on the process of enunciation itself, as opposed to that which concentrates on the outcome (the story), depicts the producers and receivers together with the processes and contexts of their operations (100-18). This “enunciative mirroring” (mise en abyme de l’énonciation)” reproduces the real-life agents and operations of filmmaking and film reception which they metonymically represent. This corresponds approximately to Casetti’s position, but, from the perspective of the story (l’énoncé), there may be a big difference.

Indeed, when the film reflected inside the film, on the intradiegetic level, is the same film being produced by the real-life creators, the enunciative mise en abyme belongs to what Dällenbach calls type III, or “aporetic mirroring.” This is the case with Federico Fellini’s Intervista (1987), in which the images and sounds we see and hear in the film are both part of the film we are watching and part of the film being produced by the director Fellini, who appears in the film as “himself”—that is, as the supposedly real-life film director of the selfsame film. Naturally, not all images coincide a hundred percent—the film also includes flashbacks where a younger Fellini, played by an actor, enters Cinecittà for the first time, but what does coincide is enough for the viewer to make the necessary aporetic correlation. This double mirroring highlights the blurring of boundaries between reality and illusion. In Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963), the relationship is even more cogent because the diegetic director, who is played by Marcello Mastroianni as an alter ego of Fellini and not by Fellini himself, does not succeed in producing the film he is preparing and aborts the project, but the extradiegetic viewers nonetheless spend 138 minutes watching a film. Thus, the redoubling does not occur inside the film, but produces itself as an extension of its outside in real-life. Metz (1972) considers this phenomenon to be the “perfect mise en abyme,” especially because of the symbiosis that occurs between intra- and extradiegetic films.

This leads Christian Metz (1991) to distinguish between “metacinema” and “metafilm.” According to him, meta-cinematic reflexivity occurs when the film mirrors aspects pertaining to the general cinematic practice, whereas metafilmic reflexivity takes place when the film evinces its own construction as a film. Contrary to Metz, I make no difference between “metacinema” and “metafilm” on the basis of the specific enunciation undertaken in particular works. I claim that all films that belong to the category of metacinema should automatically be considered meta-films. However, I do acknowledge the need to specifically name a film that mirrors its own cinematic technique in the weaving of the film proper. In this case I prefer to use the designation “self-reflexive metacinema,” despite the apparent tautology, because it enhances the author’s intentionality. Thus, in this case, the tautology is both voluntary and crucial, reaffirming the primacy of enunciation. The category of hybrid metafilms in my taxonomy characterizes itself by a deliberate staging of this situation. These films display both the inside and the outside of the film proper because they thematize this reflection, which the merely descriptive films about the industry do not do. Therefore, in fact, these films have two levels of enunciative mise en abyme.

An Enunciative Taxonomy of Hybrid Metafilms

My methodology for the creation of this taxonomy consisted in intensive film-watching; an analytical corpus composed of several hundred films was perused. The list was compiled after conducting extensive theoretical research on reflexivity and the Hollywood-on-Hollywood film genre. The corpus is subdivided into three main subcategories according to the stage of cinema each focuses on: either the production stage and the entailing creative work of filmmaker(s); the reception stage and the emotional and physiological response of viewers upon watching the films; or both, when there is a well-balanced commingling of stages in the same film.

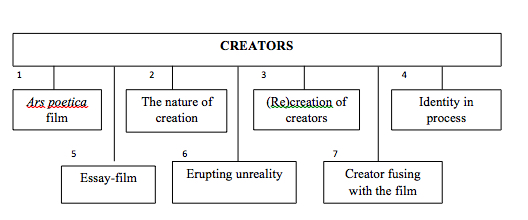

The category of creators in my taxonomy has the highest number of subcategories, which attests to the importance the creators have in a metacinematic genre, which they themselves develop. The subcategories are listed in the diagram bellow (as in the following ones), from left to right, in ascending order of complexity. Each subcategory derives naturally from the preceding one.

Figure 2. Category of hybrid films about production.

The Ars Poetica—or poetic art film—consists in a self-portrait of the creators working. Thus, their cinematic discourse on film intersects the examination of their own authorial style in process, as they are revealed in mid-work. “Cinema self-represents itself; the film self-represents itself. As for the director caught up in this type of figuration he or she becomes a specialist [homme ou femme de métier], a thinker of his or her own art, a hands-on artist who at the same time effects an act of signature” (Grange 58, my translation). This technique is particularly memorable when the stage of filmmaking depicted is that of the film shooting, the most iconic part of a director’s work.

The poetic art film is a stronghold of European cinema, but not all of these films are self-reflexive and hybrid (e.g., François Truffaut’s Day for Night/La Nuit américaine, 1973). The ones that are self-reflexive are clearly aporetic in that there is an absolute conjunction between the film-container and the one that is embedded in it. The most celebrated film in this subcategory is undoubtedly Man with the Movie Camera (Celovek c kino apparatom, Dziga Vertov, 1929). Truthfully, Vertov’s magnum opusmay be integrated in most of my subcategories of hybrid films, but I privilege the inclusion of Vertov’s opus in this specific subcategory because its images, sounds, and structure correspond entirely to the theoretical postulate formulated by Dziga Vertov himself—the Kino-Glaz[10]—and practiced as sort of personal film philosophy. The film interconnects the activities of the director, the cameraman and the film editor, revealing an all-encompassing process of filmmaking and film reception (when the film, at last, attains its viewers in a film theater, which comes alive with their presence).

The group pertaining to the Nature of Creation focuses on the essence of creation and what it may achieve. The nature of creation serves as a developing agent, in the analogue photography sense of the word. This is expressed through the alternation (via crosscutting, among other techniques) between two different production modes. Examples of this include the co-production CG (Roman Coppola, 2001) and Man of Marble (Czlowiek z marmuru, Andrzej Wajda, 1977). In the former, a young film editor directs an experimental film—in an allusion to David Holtzman’s Diary (Jim McBride, 1967)—while working on a big runaway co-production shot in Europe, reminiscent of Roger Vadim’s Barbarella (1968). The intertextual references establish an artistic confrontation between two types of cinema produced in the 1960s, where the action of the film is set. Wajda’s film, on the other hand, alternates between two types of images: film-in-the film excerpts of a popular hero of the Soviet regime, shot in black and white, and color scenes of that character’s acts as they may have taken place. The research that a female film student undertakes in order to make a documentary on the heroic figure of the proletarian hero Birkut reveals that images lie, especially when controlled by a totalitarian regime. It is up to the chief-enunciator, the film director Wajda, to make them speak truthfully. This subcategory may also include films about the shooting of other art forms, which always implies the existence of a camera and an act of cinematic recording. That is the case of The Mystery of Picasso (Le Mystère Picasso, Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1956) and Blood Wedding (Bodas de sangre, Carlos Saura, 1981).

The next subcategory concerns the deliberate rewriting of reality as a form of enunciation. The real-life cases of the German silent film pioneers, Skladanowski brothers, who preceded the Lumières, and F.W. Murnau, respectively in The Skladanowski Brothers (Die Gebrüder Skladanowski, Wim Wenders, 1995) and Shadow of the Vampire (E. Elias Merhige, 2000) value the visionary component of those pioneering praxes. These films cannot be considered strictly descriptive because they are historically dubious reconstitutions, and also because in them the acts of intrafilmic production alternate with the objects thus recorded, perceived as deliberately aged images, forming another reality in the midst of an already distorted account. For example, in Merhige’s film, life imitates art, as the filmmakers of Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922),arguably the most famous vampire movie in film history, are at the mercy of the main character who turns out to be an actual vampire. Additionally, another cluster of films belonging to this subcategory distances itself from any real-life creator, opting to engender their own creators. In Train of Shadows (Tren de sombras, José Luís Guérin, 1997), the film reproduces, through digital means, the absence of sound of early cinema, as well as the tear and wear of such films. Despite the materiality of Guérin’s film, one is confronted with the remnants of an existence, that of the 1900s filmmaker—a long-deceased director of home movies. It is through the excerpts of his films, as well as motionless shots of the empty house, episodically crossed by cars’ headlights, that the viewers feel the creator’s ghostly presence somewhere in the vicinity of his work. In short, this subcategory aims to mythify the creator.

The subcategory of Identity in Process focuses on the creation undertaken by actors, whose profession forces them to assume other individualities. The mixture between several identities begets a particular hybridity that does not originate in the same way when the creator is a film director or another member of the crew. In the latter situations, the use of a different type of image or sound to mark a filmic inner distinction tends to separate two realities, whereas in the case of an actor the use of the same body to bring different characters to life produces the opposite hybrid result. In these films, some actions are staged in such a manner as to prevent viewers from realizing from the outset (or possibly ever) if what they are watching is “real” and played by the “actor,” or “fictitious” and livedby the “character.” In the film All About Actresses (Le Bal des actrices, 2009), directed by the actress Maïwenn, who also stars in the film, the viewer is constantly unsure whether the featured actresses, playing themselves, are experiencing real neuroses or if those are just part of what is required of their roles. In another French film, Pater (Alain Cavalier, 2011), the director Cavalier and his actor friend Vincent Lindon enter into an allegorical game of political role-playing. One pretends to be the President, the other the Prime Minister. Other mutual acquaintances also take part in this game. Lindon is an actor both in the film and in real-life; Cavalier is a film director both in real-life and in the film. A director of self-portraits, used to the presence of the camera and accustomed to lending his own body as a filmic object, Cavalier, in this particular film, records himself in the skin of another, preserving nevertheless his own professional activity. Indeed, in between scenes of improvised role-playing, Cavalier films and speaks in his own name about the participation of his friend in this project.

Much has been said about Essay Films, especially about their formal innovations and their admission of an open discourse, sometimes in voice-over (but not necessarily so). In a project like Histoire(s) du cinéma (1989-1999), the director Jean-Luc Godard often appears as the dominant figure of this type of filmmaking, surrounded by film equipment and directly voicing his own ideas about cinema. Possibly, however, the most anti-illusionist form of self-reflexive essay film is to be found in Orson Welles’s F for Fake (Vérités et mensonges, 1973). The director, who was an accomplished magician, concocts an act of illusionism masking the lie(s) with the truth. Unlike Godard, when Welles uses the first person singular, he is not referring to himself as a filmmaker but as a forger. In other words, he is shielding himself behind his brand image in order to deliver a sharp discourse on illusion, which is the kernel of his cinematic practice.

The subcategory of Erupting Unreality is based on surprise, regardless of the degree of strangeness the films may possess. As the story unfolds, the works become growingly artificial, some of them culminating in total illusion such as Epidemic (Lars von Trier, 1987), Golden Dreams (Sogni d’oro, Nanni Moretti, 1981) and Berberian Sound Studio (Peter Strickland, 2012). In the latter, a British foley artist tries to adapt himself to the Italian Giallo horror cinema of the 1970s. Terrifying by nature, this film genre, which depends to a large extent on sound effects and piercing screams, proves too much violence for the soundman to stomach. Day after day, the filmic screams and the Italian ways begin to take a toll on the protagonist, who ceases to distinguish reality from fiction. Yet the film is imbued with such an ambivalence that the film viewers are equally incapable of distinguishing between the two regimes. Other films return to an economy of apparent reality in the end. For example, Ingmar Bergman’s Prison (Fängelse, 1949) contains both a film-within-the-film that pastiches a short silent slapstick comedy and an actual dream enunciated by one of the main characters, but the whole plot revolves around a film shooting. The artificiality that, little by little, imposes itself upon the film is directly connected with the dreamlike quality of cinema.

The Creator Fusing with the Film is the most complex subcategory. It may pertain to film directors as well as other creators. Examples of the former are Agnès Varda’s The Beaches of Agnès (Les Plages d’Agnès, 2008), a cinematic self-portrait (Chinita 2017), or Federico Fellini, in The Clowns (I Clowns, 1970), living up to his credo of being a natural-born liar (“Sono un gran bugiardo,” he repeatedly observes). These directors play a personaof themselves that is redoubled in the intra-diegetic film they themselves direct. In all cases, the encompassing film coincides with the embedded one. In Sally Potter’s The Tango Lesson (1997), the director “Sally” abandons a fictional high fashion project shot in colour for another more personal one on tango, shot in black and white. At the end of Potter’s film, the diegetic Sally has not managed to shoot anything, but the extradiegetic viewers have, indeed, watched a film, just like in Fellini’s 8 ½.Due to the crosscutting, the films introduce an ambiguity between what may be reality” or “illusion.” Sometimes it is as difficult for a character to tell them apart as it this for extradiegetic viewers. For example, in All That Jazz (Bob Fosse, 1979), the protagonist, who is a major choreographer and stage director on Broadway, agonizes in a hospital bed when he hallucinates his own death as a grandiose glittering musical number, because life and show are intertwined and although the former ceases the latter must go on.

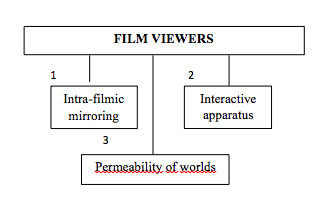

Figure 3. Category of hybrid films about reception.

The general category of hybrid films about film reception has less subcategories than that about the creator(s). This is because there is less variety here, but also due to the type of agency itself. No film viewer can direct a film about filmmaking without becoming a creator, and often when that happens, spectatorial issues are relegated to the background.

The subcategory of Intrafilmic Mirroring implies the existence of intradiegetic film(s)-withinin-the-film which reflect, formally and narratively, the issues and situations of the overall film that encompasses them. These intrafilms contain a double mirroring in that they also reduplicate the optical-scopical operations carried out by the film viewer. This double mirroring is, therefore, simultaneously supported by technical and conceptual aspects. Hybridity, in this case, results from the mixing of different types of images, each of them corresponding to a different “reality,” and from the interactive relationship between the content of those images and the subjects they supposedly represent. For example, Veronika Voss (Die Sehnsucht der Veronika Voss, Rainer Werner Fassinder, 1982) begins with a film-within-the-film depicting a story of morphine dependence in which the intradiegetic protagonist hands over all of her assets to the nurse that feeds her addiction. This film is watched by a small audience, including the actress who played the role of the morphine addict, the Veronika Voss of Fassbinder’s film title. This diegetic protagonist turns out to be addicted to morphine herself, and just like her own character, she, too, is victimized by the greed of other people, and destined to die.

The subcategory of Permeability of Worlds, which Christopher Ames calls screen passages (108-36), consists in a screen crossing undertaken by some of the film’s characters. This transposition may take place both ways, from the “real” world to the “screen world” (i.e., a film-within-the-film) and vice versa, or in just a single direction. Both worlds indicated in quotation marks above exist in the film and are, therefore, diegetic, but one of them is taken to be more realistic than the other (which is embedded as a cinematic artifice). The metaleptic intermingling of characters of different ontological status highlights the two-dimensionality and artificiality of cinema. When the diegetic viewers manage to cross the confines of the screen and join the intradiegetic characters, they become noticeably more two-dimensional; when the intradiegetic characters step out of the story and into the film theater where they are being watched, they seem to acquire volume. This interaction is combined with possible chromatic changes and with dialogue lines and looks to the camera and to whoever is watching on the other side. The aforementioned interaction involves a screen, but it does not need to be a film screen. Some examples exist in which the other side is framed by a television set, such as Stay Tuned (Peter Hyams, 1992) and Pleasantville (Gary Ross, 1998). The nature of the medium is here less important than the existence of another side of space, which corresponds to the cinematic apparatus and the face-to-face position of the film viewers in relation to the film seen. In The Icicle Thief (Ladri di saponetti, Maurizio Nichetti, 1989), for example, the diegetic film the character played by Nichetti himself is watching on TV is a pastiche of Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist masterpiece The Bicycle Thief (1948), but ontologies become muddled when the female model of a soap commercial, which keeps interrupting the serious film, accidentally intrudes upon the black and white neorealist opus. This forces “Nichetti” to follow her into the television set in order to rescue the neorealist universe from such a violation.

The subcategory Interactive Apparatus deals with the specious interaction of both sides of the film, almost as if the theater screen/television set were the extension of the “real world” and vice versa. Hellzapoppin’ (H.C. Potter, 1941) exposes, as gags, a myriad of technical issues of film projection due to the projectionist’s incompetence. At a given point, the film slips from the projector’s sprocket holes and the ensuing projection shows, in a single image, the bottom half of one film frame together with the upper half of the following frame, causing the intradiegetic characters’ legs to be seen above their torso. The interaction of the two comedian protagonists with the camera is unremitting and occurs in the form of addresses to the diegetic projectionist in the booth, to an invisible audience placed outside of view inside the film, to the intradiegetic characters, or even to the actual viewers. In Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983), in turn, an already deceased individual, addresses a prerecorded speech directly at the protagonist through the television set, as if he could still be observed and generate reactions. This type of interaction, although entirely fallacious, manages to pull the extradiegetic viewer more into the film (although it also works as a metacinematic warning of the danger of such adhesion).

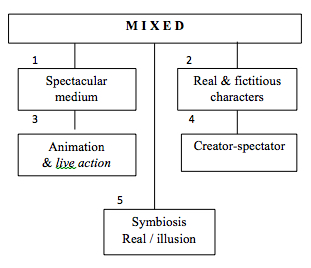

Figure 4. Category of mixed hybrid films.

The category of Mixed Films combines the transpositions and interactions of my category of Film Reception with the creativity and the identity processes involved in my category of Filmmaking. It is based on the tacit desires of the film viewers (which is to fuse with the film) and the creators (which is to express themselves through art), but it combines the two in a single product that reveals a profusion of cinematic techniques and film screens or related frames. Each of the following subcategories contains countless film objects; in all of them, the film work of the characters is mirrored in the authorial enunciation itself produced by the chief-enunciator of the whole film, and vice versa.

In the subcategory Spectacular Medium, the medium involved must perforce be audiovisual (cinema, television, video…); it may be combined with other forms of spectacle, thereby incorporating a very interesting intermedial dimension, or it may be linked only to show business. Either way, a spectacle occurs inside another one, and the embedded spectacle mirrors, formally and thematically, the containing one. The effect may be produced with two very different goals in mind. Federico Fellini’s And the Ship Sails On… (E la nave va…, 1983) and Ginger and Fred (Ginger e Fred, 1986), as well as Manoel de Oliveira’s The Satin Slipper (Le Soulier de satin, 1985) present cinema as an artistic vehicle among others. However, due to his ability to contain other art forms and match them, the power of cinema is ultimately foregrounded. On the other hand, in the US-American films Medium Cool (Haskell Wexler, 1969), Natural Born Killers (Oliver Stone, 1994) and The Truman Show (Peter Weir, 1998), what really counts is the medium’s ability to generate events, deliberately creating a reality that is profoundly illusory.

Films dealing with the intermedial spectacularity of audiovisual media have a tendency to be heartwarming and nostalgic. And The Ship Sails on… opens with a black and white poor quality photography film-within-the-film [00:24-10:11]. The slightly magenta-toned images are reminiscent of an early-20th-century newsreel (the film’s story is, indeed, set in 1914). These images belong to a reporter’s piece about several members of the operatic community about to board the ship of the film title in order to scatter on the ocean the ashes of a diva. It is through this seemingly “old” enunciation that the film viewers are introduced to the characters they will follow for the rest of the encompassing film. Suddenly, at the exact moment of boarding, the film image gradually changes to low saturated color. This gradual enunciative motion marks the rhythm of the singing voices of all the music practitioners involved in a tribute to the ashes boarding the ship, together with the ship’s crew and onlookers at the docks. The shift in color equally marks the entrance into another doubly artistic dimension: that of cinema and opera, united in the single goal of illusion. The funereal nature of And the Ship Sails on…, which ends up sinking with all its illustrious occupants on board, mourns a loss—the evolution of the medium—and traces its archeology.

The protagonist of Medium Cool, filmed in vérité style, is a news cameraman on a perpetual hunt for sensationalism. The film opens on the image of a crashed car, next to which lies a female victim, still alive [00:08-02:17]. The reporter, in a clear inversion of priorities, first records the accident and only then, taking his time, gives his partner instructions to call for help (“Better call an ambulance”). Thus, images of the woman might actually reach the television station before the real woman enters the hospital. The reporter evolves from a distanced attitude to a more participative one, which ironically dictates his own death in a car accident. Benny’s video (Michael Haneke, 1992) also dwells on the absence of feelings of the recording camera and those behind it. This time, the protagonist is a teenager boy who not only delights in watching the killing of a pig, but also ends up killing a female friend as a silly dare. The camera is kept on throughout the bloody act, which seems to take forever [24:37-28:46]. Although the murder takes partially place off-screen, the implications are quite perceptible for the film viewers, especially because the girl screams throughout.

The subcategory of Real and Fictitious interacting amply illustrates the duality on which cinema is founded. These films contain characters whose nature is less real than others in the same opus. In Play It Again Sam (Herbert Ross, 1972), Woody Allen plays the role of a film critic in love with the film Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942). Soon, an imaginary Humphrey Bogart appears advising him on his love life. The diegetic figure of “Bogie” is only visible to the protagonist and the actual film viewers, functioning as a representation of the classic Hollywood cinematic idols of the public. This is a cult phenomenon but actualized as a fantasy. In The Movie Hero (Brad T. Gottfred, 2003), the protagonist cannot cease to behave as if he were the hero of a film featuring his own life. He thus addresses the camera, trying to guide it towards the best recording position.

In the subcategory that interlaces Animation and Live Action, a gigantic metalepsis is produced. In practice, both types of characters, independently of their specific materiality, are two-dimensional, completely fictitious and coalesce in the same film, but in the story proper they belong to two different ontological universes. This interlacing reveals an important layer of technical production, although the animators are not seen at work in the film itself. However, for the produced film object to be considered a mise en abyme—a prerequisite of hybridity in my taxonomy—the story needs to be connected to the show business, especially the film industry, as is the case with Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (Robert Zemeckis, 1988). It is also the case of the Italian film To Want to Fly (Volere volare, Maurizio Nichetti and Guido Manuli, 1991), in which the protagonist, a foley artist of animated films, played by Nichetti himself, is progressively transformed into a cartoon character, which naturally inconveniences his romantic life.

The subcategory of Creator-Viewer agglutinates the activities of film production and film reception in a single character and possibly a set of characters, who act as his/her extensions. One of the ways to obtain such a conjunction implies the existence of psychic enunciation, as in The Science of Sleep (La Science des rêves, Michel Gondry, 2006) and The Adventures of George the Projectionist (Tim Higham, 2006), in which characters dream a substantial part of the action. The psychic enunciation redoubles in essence the physical enunciation by the real-life creator. Living in Oblivion (Tom Di Cillo, 1995) discloses the modus operandiof the North American indie film, but also contains three embedded narratives, each of them a dream by one of the main characters (the Director, the Main Actress, the older actress playing the Mother in the film). These dreams, which are only revealed as such after the fact, are shown in black and white while the diegetic shooting is portrayed in color—and correspond to different versions of the events of the day about to start. The second way to obtain this conjunction presupposes that the diegetic viewer is also a creator or a member of the film industry, as is the case in Peeping Tom (Michael Powell, 1960), and Brian De Palma’s Hi Mom! (1970) and Blow Out (1981). All of these films contain films-within-the-film or diegetic shooting scenes that reduplicate, visually and thematically, one film in the other.

The subcategory of Symbiosis between Reality and Illusion corresponds to Christian Metz’s perfect symbiosis, the enunciative state in which the double mirroring makes virtually indiscernible the “illusion” and the “reality,” amalgamating the whole into one single substance: unreality. Several filmmakers (Jean-Luc Godard, David Lynch, Abel Ferrara, Steven Soderbergh and Carlos Saura) provide this film group with more than one example. The profusion of technical equipment, narrative levels, reversible or ambiguous identities, layers of unreality, and so forth, is such that film viewers are permanently made to doubt the nature of what they see and still manage to be surprised. In this case, the filmic enunciation is precisely made of this fluctuating and volatile reality. These films are essentially aporetic, equivalent to Lucien Dällenbach’s type III mise en abyme in which the reflected film is the very same film being watched by the film viewers, and both films are constructed, step by step and at the same time, to the point of being completely indistinguishable from each other.

Conclusion

As Dziga Vertov once put it: “Everyone who loves his art, always searches for the essence of its techniques” (quoted by Stam 1981, my translation). No wonder the hybrid metafilms are the essence of metacinema, because in them the artists do not look for reality or just storytelling; they look for the materiality of expression whereby they find themselves. The realistic metaphor of the mirror as a reproduction of reality is one of the biggest fallacies of the seventh art. In real life, a mirror always reflects an inverted image, just as the images picked up by the eyes are reflected upside down in the human retina (Descartes 112). Fiction film—which interests me most, although not all metacinema is strictly fictional, as I said before—is a medial undertaking, entirely dependent on technical reproduction, both in the recording and the exhibition stages. According to Vivien Sobchak (1992), the two most important machines in filmmaking—the camera and the projector—are extensions of the human eye endowed with a double functionality. On the one hand, they allow people (creators or film viewers) to see more, enhancing through technical means elements which the anatomical eye is incapable of recording. On the other hand, they enable a different sort of vision, as the images retained belong to another. The same could be said of sound, of course. In other words, cinema is one big lie that always tells the truth about its creators. Self-reflexivity in this aspect is tantamount to self-revelation.

Fátima Chinita

Works Cited

Ames, Christopher. Movies About the Movies: Hollywood Reflected. The University Press of Kentucky, 1997.

Anderson, Patrick Donald. In Its Own Image: The Cinematic Vision of Hollywood. Arno Press, 1978.

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author” (1967). Trans. Richard Howard. http://www.tbook.constantvzw/wp-content/death_authorbarthes.pdf, Accessed on 23 October 2012.

Benveniste, Émile. “L’Appareil formel de l’énonciation ?” Langages, vol. 17, 1970, pp. 12-18.

Bordwell, David. Narration in the Fiction Film. University of Wisconsin Press, 1985.

Casetti, Francesco. “Cinema in the cinema in Italian Films of the Fifties: Bellissima and La signora senza camelie.” Translated by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, Screen, vol. 33, no. 4, 1992, pp. 375-93.

Cerisuelo, Marc. Hollywood à l’écran, les Métafilms américains. Presses de la Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2000.

Chinita, Fátima. “Agnés Varda’s Recycling of Life: Meta-cinema as Discourse on Creatorship.” New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film, vol. 15, no. 1, 2017, pp. 63-79.

—. “Do Meta-cinema Auto-Reflexivo como forma de enunciação autoral,” two volumes. 2013. Lisbon University, PhD dissertation.

—. O Espectador (In)visível: Reflexividade na óptica do espectador em INLAND EMPIRE de David Lynch. Editora Livros Labcom, 2013.

Dällenbach, Lucien. Le Récit spéculaire : Essai sur la mise en abyme. Éditions du Seuil, 1977.

Descartes, René. “La Dioptrique.” 1637. Discours de la méthode plus La Dioptrique, Les Météores et La Géométrie qui sont des essais de cette methode, 350th anniversary edition, Librairie Arthème Fayard, 1987, pp. 69-208.

Foucault, Michel. “What is an author?” (1969). Slightly modified version. Translated by Josué V. Harari, http://pt.scribd.com/doc/10268982/Foucault-What-is-an-Author. Accessed on 22 March 2021.

Fredericksen, Don. “Modes of Reflexive Cinema.” Quarterly Review of Film Studies, vol. 4, no. 3, 1979, pp. 299-320.

Gaudreault, André. Du littéraire au filmique, système du récit. Méridiens Klincksieck, 1988.

Grange, Marie-Françoise. L’Autoportrait en cinéma. Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2008.

Jost, François. “Un monde à notre image. Énonciation, cinéma, télévision.” Études littéraires, vol. 26, no. 2, 1993, pp. 105-15.

—. “Godard, professionnel de la profession.” In Godard et le métier d’artiste, edited by Gilles Delavaud, Jean-Pierre Esquenazi, and Marie-Françoise Grange, L’Harmattan, 2001, pp. 335-43.

Habib, André. “Notes sur la cinéphilie (1): Avant, Après – De l’actualité ou de l’inactualité de la cinéphilie”. Hors Champ on line, March 2005, http://www.horschamp.qc.ca/article.php3?id_article=173. Accessed on 12 April 2007.

Metz, Christian. “A Construção « em abismo » em Oito e Meio de Fellini.” 1966. In A Significação no Cinema. Translated byJean-Claude Bernardet, Editora Perspectiva, 1972, pp. 217-24.

—. L’Énonciation impersonnelle ou le site du film. Méridiens Klincksieck, 1991.

Mouren, Yannick. “Le film art poétique, sous ensemble du film réfléxif.” In Le cinéma au miroir du cinéma. CinémAction-Corlet Publications, 2007, pp. 114-24.

Schmidt, Nicholas. “Les usages du procédé de film dans le film.” In Le Cinéma au miroir du cinéma, CinémAction-Corlet, 2007, pp. 102-13.

Sobchak, Vivian. The Address of the Eye: A Phenomenology of Film Experience. Princeton University Press, 1992.

Sojcher, Frédéric. Cinéastes à tout prix. Imagine, DVD, 2004.

Sontag, Susan. “The Decay of Cinema.” The New York Times online, 25 February 1996, http://partners.nytimes.com/books/00/03/12/specials/sontag-cinema-html. Accessed on 17 August 2004.

Stam, Robert. O Espetáculo Interrompido: Literatura e Cinema de Desmistificação. Translated by José Eduardo Moretzsohn, Paz e Terra, 1981.

—. Reflexivity in Film and Literature: From Don Quixote to Jean-Luc Godard. Columbia University Press, 1992.

—. Film Theory: An Introduction. Blackwell Publishing, 2000.

Sterritt, David, ed. Jean-Luc Godard: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 1998.

Tőrők, Jean-Paul. “Le cinéma dans le cinéma.” L’Avant-Scène Cinéma, vol. 216, 1978, pp. 25-28, pp. 33-36.

Vertov, Dziga. “Instructions provisoires ax cercles Ciné-Oeil” (1926]). Cahiers du Cinéma, vol. 226, January 1971, pp. 12-17.

Withalm, Gloria. “’You turned off the Whole Movie!’ – Types of Self-Reflexive Discourse in Film,” 2000, http://www.uni-ak.ac.at/culture/withalm/wit-texts/wit00-porto.html. Accessed on 16 March 2021.

[1] André Habib claims that in the 1960s and 1970s, both in Europe and North-America, young cinephilic viewers took on their love for film from cinephilic filmmakers such as Godard, among others (no pag).

[2] Although filmmaking is a collective enterprise—except for experimental films which may be truly solo creations on the part of one artist—the main expressive voice in the film is the director’s (at least in arthouse cinema). His or her vision ties together all the other personal expressions noticeable in the film: those of the heads of department, such as the cinematographer, the editor, the production designer, etc. This position is based on the Cahiers du cinéma’s credo of the auteur, but is not entirely coincident with it, as it has empirical and legal ramifications that transcend the cult of the artist. The main point of contact is the existence of a living person who is responsible for the coherent artistic universe contained in the film and responsible, to a great length, for the self-reflexivity manifest in the work.

[3] Yet considerations that are not directly linked to the artists’ profession and their artistic path are irrelevant.

[4] Opposed to this, in Benveniste’s theory, is the “story” (histoire), the neutral presentation of facts.

[5] Although film is not a language because these resources are not stable.

[6] For example, Nicholas Schmidt’s definition of met-film is the contrary of Marc Cérisuelo’s, for whom it refers to works depicting the film industry that are not grounded on reflexivity (19). For Cérisuelo, films that are based on the dichotomies reality/imagination and dream/reality, as well as mises en abyme (among other things), are excluded from this category.

[7] Notwithstanding, documentary is becoming growingly hybrid, in keeping with the general cinematic tendency of postmodernity and the expanding practice of essay films.

[8] Some documentaries may—and do—fulfil this latter condition, which requires an adulteration of reality.

[9] Original text: “un retour du cinéma sur lui même.”

[10] The Kino-Eye (Vertov 1926) is a theory and practice that posits the use of the camera to register and explore the visual facts better than the human eye could, thus penetrating deeper into the visible world. Since the camera was invented by the bourgeoisie, it was necessary to put it to different uses and to resort to film editing as a means to organize the visible world in order to provide the masses with the perception of a new reality.