I first encountered Algiers through the childhood memories of a Palestinian friend who grew up there until she was fourteen years old.1 Algeria became her family’s home in the 1970s, when the Israeli authorities revoked her father’s residency after he had spent some time studying abroad.2 For many years, he was denied access to his homeland, where many of his family and friends still lived. When I arrived in Algiers in 2022, I was vaguely aware that there was something special about Algeria’s relationship with the Palestinians, whose struggle it associated with its own. In fact, Algerians had not been fighting against French colonialism alone during their war of independence, but against imperialist structures worldwide. They had considered their struggle, from the outset, as part of the collective resistance of oppressed peoples around the globe. The stakes were high, and the commitment to other peoples’ liberation meant much more to them than merely a historical parallel or a political alignment. For independent Algeria, solidarity with the Palestinian cause became even a matter of state, enshrined in the 1976 National Charter: “The liberation of Palestine is at the heart of our conscience and our concerns”, it reads. “Our total commitment to the Palestinian people and to other Arab peoples whose territories are occupied is for us, more than a duty of solidarity, an act identified with our own liberation. Therefore, this commitment is unreserved and implies the acceptance of all sacrifices, including those of blood”.3 It comes as no surprise, then, that the PLO, founded in 1964, maintained a very active office in Algiers, right in the heart of the city, and that it was there, in 1988, that Yasser Arafat proclaimed the State of Palestine.

With that in mind, I expected to find an abundance of publications testifying to this special relationship with Palestine in Algiers. But my research efforts did not go very far. Although the local booksellers and antiquarians were remarkably knowledgeable and very forthcoming, they could not find much to suggest on the subject. When I mentioned that I was interested in the Palestinian question and its relation to Algeria, however, their faces immediately lit up, as if I had evoked close companions or intimate memories. In all my conversations, whether with book professionals, Algerian friends, taxi drivers, vegetable sellers, or spontaneous encounters, everyone seemed particularly moved by the plight of the Palestinians and fervently supportive of their cause. A kind of collective solidarity shone through, grounded in an emotional bond that transcended the sphere of political opinion. This even shows in the national team’s soccer matches, which regularly turn into demonstrations of solidarity:4 when the Algerian players win, they hoist, alongside with the Algerian flag, also the Palestinian one and their keffiyehs. What is more, supporters sing a special song with the evocative title “Falasteen Chouhada” (“Palestine, Land of the Martyrs”), a song that is “another staple of the Algerian national team”, as Algerian journalist Maher Mezahi explains to Aljazeera. “‘The Algerian national team has sort of become the vehicle for the advocacy of the Palestinian cause in all of Algeria.’ The chant became so popular that Algerian fans supported the Palestinian team against their own side in a friendly match in 2016 that saw more than 70,000 fans attend the game. The stadium erupted in euphoria after the Palestinian side scored, and for many, this could not better encapsulate Algerians’ love for Palestine.”5 This collective passion for a team from a country other than their own is certainly extraordinary in the world of football, especially as it is first and foremost about the people it represents rather than the performance of the players. But this is not the end of the song’s story. Actually, it is derived from another song, “Bab El Oued El Chouhada”, which commemorates the murder of more than 500 Algerians by the Algerian government security forces in 1988 for demonstrating against their appalling living conditions in the Algiers neighborhood of Bab El Oued.6 “Falasteen Chouhada” thus refers to both the ongoing struggle of Palestinians and that of Algerians against the injustices and violence inflicted upon them by their own government. Singing this song collectively draws a line of solidarity between oppressed peoples against the oppressive powers that try to muzzle them. In a way, it is a denunciation of the Algerian state, reaffirming the collective principles on which it was built and on which it prides itself, but which it is betraying against its own people.

This impressive solidarity of the Algerians with the Palestinians struck me deeply. Where did it come from? How can it be grasped today, in a world where the omnipresent “capitalist realism” seeks to stifle all utopian thinking from the cradle, long after the active struggles of decolonization and the glorious years of “Algerian Algeria”?

Drawing a different map: Third Worldism, internationalism, non-alignment

To understand all this better, I began to delve into books on Algerian history and personal testimonies and memories from that period. I began to realize that the idea and practice of solidarity was central to the struggle for independence from the outset, and also to the founding of the nation. Defeating the French colonizers, with their powerful army, their NATO allies, and their cultural, political, and economic hegemony, was unthinkable without the support of other world powers, and the fighters of the National Liberation Front (FLN) were well aware of this. The internationalization of the conflict was in fact its secret weapon, as Matthew Connelly shows.7 Its main objective was to make the Algerian people’s cause known to the world and to sway international public opinion in its favor. Therefore, the FLN had offices in many countries and participated frequently in meetings of international organizations, notably in 1955 at the Bandung Conference, the first to bring together, under the aegis of India’s Jawaharlal Nehru, Egypt’s Abdel Nasser and China’s Zhou Enlai, representatives of some thirty recently decolonized Afro-Asian countries. Refusing to side with either of the major Cold War blocs, these countries sought to create an alternative international force beyond the antagonistic superpowers. Although the Algerian delegation was only present as an observer, it succeeded in getting the final motion to state its explicit support for Algerian independence.8 At the subsequent conference in Belgrade in 1961, the first to be officially called Non-Aligned Movement Summit, Algeria was already admitted as an active participant, even though it had not yet officially achieved independence and was represented by a provisional government. At the UN, the so-called “Algerian question” had been discussed frequently since 1955, until in 1961 the FLN succeeded in passing a resolution in favor of Algerian independence by a vote of 63 to 0, with 38 abstentions.9 According to Benjamin Stora, “the Algerian war was won above all politically by the Algerian nationalists. What they failed to do on the battlefield, they did on the field of international diplomacy.”10

The Algerian resistance also relied on other countries for material support. Its weapons came mainly from Egypt, but also from other states such as China and the Soviet Union. Its training camps were located in Mali, Tunisia, and Morocco, and also hosted activists from other liberation movements from Niger, Congo, Angola, and the African National Congress, which was fighting against the apartheid-system in South Africa (Nelson Mandela, then head of the ANC’s armed wing, was among those who joined). “The FLN was already an inspiration to other anticolonial movements on account of its accomplishments, but the openness of its assistance program to smaller movements earned it a great deal of additional goodwill and credibility in Third World circles,”11 writes Jeffrey James Byrne in this regard. As a result, the Algerian struggle became the emblem of anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggles on a global scale. Frantz Fanon, Martiniquais who declared Algerian his adopted country and a great thinker on the Algerian revolution in particular and anti-colonial movements in general, embodied this “symbiosis between Third World internationalism and Algerian nationalism”12 to perfection. He maintained that there could be no liberation of a people without the destruction of the global capitalist and imperialist structures that confined them within exploitative relations. In 1958, at the African Peoples’ Conference, he declared: “It is not possible, according to us, confronted as we are with implacable imperialist designs, to pursue a policy to engage in a particular arrangement with colonialist forces. […] An Algerian cannot be really Algerian if he does not feel in his innermost self the indescribably horrible drama that is unfolding in Rhodesia or in Angola.”13 The struggle was global, or it was not. Solidarity among the world’s “wretched of the earth” was its condition of possibility.

This internationalist orientation remained at the heart of Algerian politics after the FLN’s victory over the French colonizers. At the end of the war, Algeria found itself in an unprecedented, very complex situation. Defeated by those they had oppressed, the former colonial regime adopted a policy of scorched earth, and destroyed the resources essential to the functioning of the state, including libraries, schools, and hospitals.14 The vast majority of the pieds-noirs, who until then had constituted almost the entire skilled workforce responsible for running the country’s infrastructure, had left the country in the wake of Algeria’s independence, leaving a vacuum that was difficult to fill. By the end of the war, approximately 86% of Algeria’s male and 95% of its female population were illiterate, and most of them lived in poverty.15 Algeria relied heavily on foreign support to rebuild the country. In addition to financial and humanitarian aid from many countries of all political persuasions, doctors, professors, engineers, etc. came from Cuba, Yugoslavia, France (the pieds-rouges), and elsewhere to help rebuild the country.

But most importantly, the young nation was proud of the tenacity of its fighters and the Algerian people’s solidarity. Gripped by a kind of feverish euphoria, a collective enthusiasm, Algeria was experiencing a moment of openness and freedom, where anything was possible because nothing had been established yet. “It was like a collective body, a collective individual, a people, were breathing in their own atmosphere again”, explains Daho Djerbal, “It was an immense breathing of an entire people.”16 Some parameters for building the future soon began to take shape: self-determination of course, and socialism, which was seen as the fairest system for the Algerian reality, but also lasting solidarity with other populations under the oppressive influence of colonialism, racism and imperialism. “Our country, born in the struggle against the colonizer, was carried to the baptismal font by the brotherhood of oppressed peoples from all continents”,17 writes Wassyla Tamzali. “At the beginning, didn’t Algiers seem to us to be the city that would usher in a new and fraternal era as far as the Americas and Africa? Everything led us to believe it, everyone said it, the poets, the politicians, the singers, the soothsayers. Algiers the brotherly, the cosmopolitan, the revolutionary, Algiers the African, the Arab, Algiers the non-aligned, the capital of the Third World! The adventure did not end at the gates of independence; the liberated Algerians continued to look down on the Western world. ‘Algiers will celebrate the liberation of all’: the presidents who followed one another all said the same thing. Boumediene after Ben Bella, it was the same promise.”18 Even the national charter is quite explicit on this subject: “As a Third World country, Algeria stands in solidarity with all the peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America for their political liberation, the consolidation of their independence and their economic and social development. To the best of its ability, it will spare no effort to provide practical assistance to those fighting for their freedom. It will take all initiatives likely to mobilize the forces of the three continents, in a united struggle around common objectives, to impose respect for and the guarantee of the rights of their peoples.”19 In the Algeria of the 1960s and early 1970s, this was not just an idle phrase. Palestinians were far from alone in settling in the Algerian capital. By this time, Algiers had become a “Mecca for revolutionaries”, in the famous words of Amílcal Cabral, the “African Lenin”,20 as Mehdi Ben Barka called him, and co-founder of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), who resided there on several occasions. Many politicians passed through Algiers to consolidate their political alliances, including Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, who were, especially the latter, personal friends of the Algerian president; Abdel Nasser, father of pan-Arabism; and Tito, whose distinctive socialist orientation served as a model for Ben Bella. In addition to these official visits, the Algerian government had shown unparalleled hospitality to persecuted personalities, many of whom are considered terrorists in the first world, and to liberation movements and resistance fighters against neo-colonialism and apartheid from all over the world. Algeria’s support for them was considerable: the state not only provided accommodation and diplomatic privileges, but also financed their stay. It was also an active supporter of exchanges between them: “The Algerians encouraged the numerous liberation movements they supported to coordinate with one another and facilitated voyages to Belgrade, Peking, and the capitals of other potential benefactors around the world. They called on African countries to support the Palestinian cause and put Angola, Congo, and South Africa on the agenda of the Arab League.”21 The ambition of independent Algeria was nothing less than to organize solidarity among oppressed peoples, to unite what colonialism and capitalism sought to divide, and to gather collective forces to reshape the world. The offices of some of the liberation movements, such as the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (P.R.G.), the National United Front of Kampuchea (FUNK), and Arafat’s PLO, virtually enjoyed embassy status.22 While Algeria had cut its diplomatic relations with the USA from 1967 to 1974 following the Six-Day War, the international section of the Black Panthers23 occupied an office there and formed alliances with the Vietnamese and Palestinians against “Babylon,” the American regime, aggressor in Vietnam, chief ally of Israel, and the driving force not only behind the oppression of minorities at home, but also behind neo-colonial exploitation worldwide and the establishment of dictatorial regimes in many recently decolonized countries. Another part of this front against the so-called Western bloc were the Brazilian Revolutionary Communist Party (PCBR), which had been fighting clandestinely against the fascist military dictatorship installed in 1964 (with the support of the United States), and the Chadian FROLINAT (National Liberation Front of Chad), which was combatting its own neo-colonial regime. All the movements present in Algiers at that time shared an anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist, and anti-racist orientation. The Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO), the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and Cabral’s PAIGC organized their struggles for national independence against Portuguese colonial rule. Together with the Portuguese National Liberation Front (FPLN), which was fighting Salazar’s fascist regime from within, they formed a revolutionary alliance against Portugal and geopolitical structures such as NATO, whose members continued to supply it with arms. The South African ANC and other armed movements operated out of Algiers in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and Namibia. In addition to these major movements, there were also marginal organizations such as the Liberation Front of Québec (FLQ) and the Canary Island Independence Movement (MPAIAC), which sought to detach the Canary Islands from Spain in order to free its local population from expanding mass tourism. For a brief period of time, Algiers had become the center of revolutionary energy, determined to change the rules of the world through collective struggle. The essential means for defeating the great imperialist powers and radically changing the structure of the world was the consolidation of solidarity among militants from all over the world, regardless of their skin color or origin.

Solidary Cultures

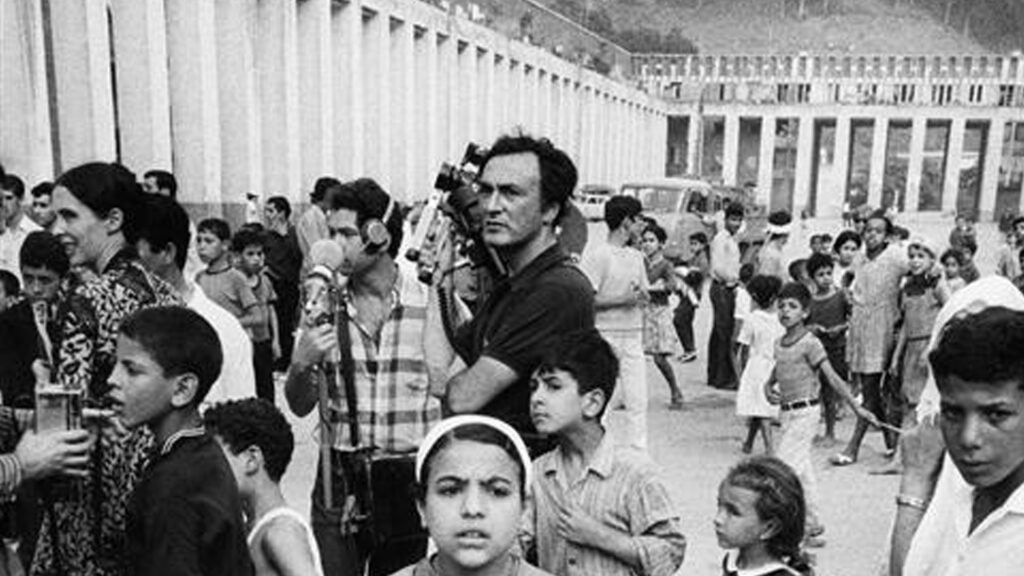

Shooting of Festival Panafricain d’Alger 1969 (William Klein, 1969).

Cultural expression was a major element of resistance in the Third World. The intertwining of armed struggle and cultural production was assumed on many levels. While cultural production was a powerful means for political education and a catalyst for mobilization, the liberation struggle represented a necessary step in creating the material conditions for the full development of a culture of one’s own. Activists had clearly understood that it was necessary to undermine the hegemonic culture imposed by the colonizers, which had been a mighty instrument for the consolidation of their domination through the ratification of the alienated self-perception of the colonized. Indeed, colonial regimes were well aware of the persuasive force of artistic media, especially film. A popular art form accessible to all, cinema was deemed a useful means of convincing the colonized of their inferiority. “Sooner or later, the inferior man recognizes Man with a capital M; this recognition means the destruction of his defenses. If you want to be a man, says the oppressor, you have to be like me, speak my language, deny your own being, transform yourself into me.”24 Breaking away from such stereotypes and normalized ideas and confronting the biased images of the imperialists with popular images of the lived reality of the oppressed and the revolutionary aspirations of their struggle was essential for political emancipation. In Algeria, the war of images intensified with the outbreak of the armed struggle. Whereas the French showed comedies to entertain the masses and distract them from the ongoing struggle, and increasingly produced documentaries to convince the “natives” of their benevolence and superiority,25 the FLN created a film unit to document the conditions of the battles and to propagate its cause. Among the unit’s filmmakers was René Vautier, a former French Resistance fighter who joined the Algerian front during the war. In the early days of Algeria’s independence, he also initiated the ciné-pops campaign, mobile screenings that, in Vautier’s words, “were intended to introduce people to progressive cinema in order to support them in their march towards socialism through the semantic illustration of the aspects of discourse specific to this form of socio-economic organization.”26 Independent Algeria quickly nationalized the existing cinemas and created structures for national production and distribution. The first Algerian films were concerned with rewriting the country’s colonial history from the point of view of the colonized – sometimes with explicit reference to ongoing global struggles against the imperialists, as in Ahmad Rachedi’s “L’Aube des damnés” (“The Dawn of the Damned”), released in 1966. Many cinematic productions dealt with the war of liberation,27 most famously the Italian-Algerian co-production “The Battle of Algiers”, directed by Gillo Pontecorvo in 1965 during Boumediene’s coup and released in 1966, which became the emblematic film of Algerian urban guerrilla warfare. Since its release, the film has influenced liberation movements around the world. In France and Israel it had been censured for several years, while the U.S. military regularly used it to understand guerrilla tactics and derive counterinsurgency strategies.

In 1965, Algiers’ Cinémathèque had been established. It was dedicated, in the words of its first director Ahmad Hocine, to “actively supporting revolutionary causes around the world”.28 Backed from the outset by Henri Langlois, who said that “[n]o film library in the Third World can compare with it either in terms of its audience or its activities”,29 it soon became the epicenter of arthouse cinema in the region. “The Cinémathèque was fully booked every night”, writes Wassyla Tamzali, herself a regular visitor. “Everyone came to collect their share of the dream. Some debated world affairs and revolution, with pugnacity and with the greatest, Godard, Miguel Littin, the Chilean, Barbet Schroeder, the Swiss, Eustache, who came to present ‘La Maman et la Putain’, Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, Gutiérrez, from Cuba, Youssef Chahine, the Alexandrian, surrounded by his pimply-eyed young actors, a soft Arab version of the Pasolinian lover, Djibril Diop and Sembène Ousmane, our African brothers, and so many others…”30 In the Cinémathèque of the ’60s – proudly the only one in the world whose law specifies that it is not subject to state censorship31 – audiences were eclectic and debates lively. “ ‘It was the place to be. Speech was free’, recalls filmmaker Sarah Maldoror. By dint of watching films ‘you’d never see anywhere else’ and verbally sparring ‘with terrible bad faith’, regulars at the Cinémathèque gradually learn, she says, to ‘distinguish technique from politics’ and know how to judge ‘whether a film is good or bad, whoever the director is.’”32

The Pan-African Festival of Algiers in 1969, of which William Klein’s eponymous film is a precious testimony, was undoubtedly the most extraordinary cultural event in Algiers during the first years of independence. It was organized by the Organization of African Unity (OAU), which was chaired at the time by Algerian President Houari Boumediene. During the Panaf’, as it is often called, a huge parade with representatives from all the participating countries filled the streets of the city, as well as performances, concerts, exhibitions, film screenings and other events. The Cinémathèque, which had become the “Mecca of Third World cinema”,33 as Ahmed Bedjaoui put it, had programmed an extensive cycle of African films, as well as a major symposium. One of the outcomes of the latter was the creation of the Pan-African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPAC), dedicated to promoting African cinema, defending persecuted filmmakers, and urging African states to develop structures to facilitate proper national film production. This was not the only meeting of African filmmakers in Algiers. Four years later, in 1973, the Third World Filmmakers’ Meeting was held here in parallel with the Fourth Non-Aligned Summit. The issues they addressed included the politics and economics of the regional film industry as well as the emancipatory potential of their art. Imperialist commercial cinema, especially Hollywood, which economically and ideologically dominated the world film market, was the great antagonist for these filmmakers. The obstacles they encountered were many and varied: on the one hand, the national production structures of their countries were still underdeveloped. Without political motivation on the part of those in power to change this situation, it was impossible for them to truly transform the sector towards a national cinéma d’auteur. On the other hand, international capitalist companies were investing heavily in Third World markets, and it was their productions – those of the cultural industry – that kept the cinemas going. Despite these problems, filmmakers were attempting to find ways out – by creating alternative distribution structures, promoting co-productions and other collective efforts to build solidarity. But the enemy – globalized capitalism – is able to adapt to the most diverse conditions, as we all know. Algeria’s golden age of solidarity lasted only a few years, during which political and social antagonisms became increasingly apparent. In his major book on Algerian cinema, published in 1980, Iofti Maherzi notes that “cinema is in crisis, doomed because it is deprived of aid.”34

What remains of solidarity

Iconic songs like “Ana hora fi El Djazair” (“I am free in Algeria”), sung by “Mama Africa” Miriam Makeba, and a few street names – Boulevard Ernesto Che Guevara, Rue Patrice Lumumba, Avenue Ho Chi Minh – still evoke this extraordinary period, when solidarity between the oppressed became a lived reality in Algiers for a brief period. Of course, not everything was as rosy as it might seem in the Algeria of the 1960s and 70s, not at all. Signs of the country’s growing inwardness, the limits of its tolerance, and its increasingly repressive Islamization were already visible.35 But there was a time in Algeria’s history when, despite internal divisions, despite complex challenges, and despite geopolitical and economic struggles, there was a real openness for change. In his afterword to the 2002 French edition of Fanon’s “The wretched of the Earth” Mohammed Harbi asks: “Were we wrong, we who thought that capitalism was not an unsurpassable horizon? Bureaucratic socialism has lived. So has Third Worldism. Its defeat, preceded by numerous tragedies and an unprecedented devaluation of human life, suits all those in the West who feared for their privileges when the initiative shifted to the side of the ‘oppressed peoples’ in the 1960s.”36 But to prove that the world order could have been different, or could still be different, is in itself a great achievement. From today’s perspective, in a world where “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”,37 where every utopian spark is immediately recovered and turned into a slogan, this confidence in international solidarity seems as audacious as it is salutary. Those who experienced the unique atmosphere of the Red Years in Algiers still thrive on it, and those who encounter its remnants are until today inspired to rediscover the meaning that the word “revolution” might once have had. Perhaps it is no coincidence that contemporary artists such as Bouchra Khalili38 and Zineb Zedira39 are exploring this unique situation through new artworks. And: “[w]hen millions of Algerian people took to the streets (in ways that somewhat recall the massive revolts of December 1960 in Algerian cities) to demand the end of a military oligarchic regime half a century later, they did not do so as a form of rupture with the Revolution’s legacy, but rather as a reactivation of the spirit of immense possibilities that 1962 had offered”,40 as Léopold Lambert writes. And then, of course, there is Palestine, whose people are the only ones of those present in Algiers in the sixties and seventies who never had the option of living in their own independent state. Instead, they have been violently divided and separated, with those in the West Bank continuing to live under an ever-worsening military occupation and those in Gaza now, as I finish this text, facing the threat of annihilation in a genocidal war. But while this unspeakable catastrophe of the Palestinian people unfolds before our eyes every day, something else is happening. While many of the so-called Western powers – especially the U.S., Germany and Great Britain – continue to facilitate this war by sending arms and providing diplomatic cover, South Africa, the country that has succeeded in abolishing the apartheid regime that ruled until 1991, is taking Israel to the International Court of Justice, the highest court in the world. At the same time, Israel’s ongoing occupation of the Palestinian territories is under scrutiny in a separate ICJ case, called for by the UN General Assembly in 2022, to which more than 50 countries, many of them former colonies, are submitting legal arguments. Those Arab countries that have normalized relations with Israel are being pressured by their own people to reconsider their position, and those that had planned to join the Abraham Accords in the near future are being forced by their populations to halt negotiations as long as the fate of the Palestinians remains as precarious as it is now. Calls for boycotts, sanctions and divestment by the BDS movement and others, reminiscent of those that led to the collapse of the South African apartheid system, are growing louder, and the criminalization of such actions in some countries, is increasingly losing its legitimacy in the eyes of the world. And most crucially, Arab, Jewish and Queer organizations around the world, along with Black Lives Matter and many other anti-racist, anti-imperialist or human rights movements, are joining forces to build a global network of solidarity with the Palestinian people, despite the violent repression they face in many places. With Walter Benjamin, who insisted on the “weak messianic power [we have been granted] to which the past has a claim,”41 we may see a sign of hope here.

Stefanie Baumann

1 This work is funded by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia under the project EXPL/FER-FIL/0045/2021.

2The first version of this paper was published in Baumann, Stefanie. “Alger solidaire”. Suspended Spaces # 6 TRAVERSER – Marseille / Alger / Ghardaïa 2 (2023).

3Front de Libération Nationale, Charte Nationale, République Algérienne Démocratique et Populaire, 1976, p.110, translated from French by the author.

4Thanks to Amina Menia and Mounir Krinah for drawing my attention to this particular feature.

5Linah Alsaafin et Ramy Allahoum, “What is behind Algeria and Palestine’s footballing love affair?” Aljazeera, 20 décembre 2021, available online : https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/12/20/algeria-palestine-football-arab-cup-2021 (accessed February 23, 2024).

6Ibid.

7See Matthew Connelly. A Diplomatic Revolution: Algeria’s Fight for Independence and the Origins of the Post-Cold War Era. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

8See for instance Boutros Boutros-Ghali, Le mouvement afro-asiatique, Paris, PUF, 1969, pp. 66.

9On the work of the New York office of the FLN, see Elaine Mokhtefi, Algiers, Third World Capital: Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers, London: Verso, 2018.

10Benjamin Stora. Imaginaires de guerre. Algérie-Viêtnam, en France et aux Etats Unis, Paris, La Découverte, 1997, p. 53, translation by the author.

11Jeffrey James Byrne, Mecca of Revolution. Algeria, decolonization and the third world, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 108.

12 Ibid., p. 2.

13Frantz Fanon, “African Countries and their solidary combat”, in Alienation and Freedom, Edited by Jean Khalfa and Robert J.C. Young Translated by Steven Corcoran, London, New York, Oxford, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018, pp. 633-635, p. 634.

14See for instance Catherine Simon, Algérie, les années pieds-rouges, Paris, La Découverte, 2020, pp. 49.

15See for instance Nadia El Kenz, L’odysée des cinémathèques : la cinémathèque algérienne. A la recherche d’une mémoire perdue (de Meliès à Lakhdar Hamina), Alger, Éditions ANEP, 1998, p. 95.

16“Before, during, and after the Revolution: a personal and Internationalist lens. A conversation with Daho Djerbal, translated from french by Hicham Touili-Idrissi” in The Funambulist n°42 : Algerian independence and global revolution 1962-2022, July-august 2022, pp. 32-41, p. 36.

17Wassyla Tamzali, Une éducation algérienne. De la revolution à la décennie noire, Paris, Gallimard, 2022, p. 112, translation by the author.

18Ibid., p. 216.

19Charte nationale, op.cit., p. 109.

20 See Saïd Bouamama, Figures de la révolution africaine. De Kenyatta à Sankara, Paris, Zones, 2014.

21Byrne, Mecca of Revolution, op. cit., p. 175.

22 See Claude Deffarge & Gordian Troeller, “Alger, capitale des révolutionnaires en exil “, Le Monde, August 1972, pp. 6-7, as well as their film “Algier – Hauptstadt des Revolutionnäre”, broadcasted in 1972 at the German television channel NDR.

23See also Mokhtefi, Algiers, capital of the revolutionnaries, op.cit..

24Juan José, Hernandez Arregui, « Imperialismo y cultura”, quoted by Solanas Fernando et Octavio Getino in “Towards A Third Cinema: Notes and Experiences For The Development Of A Cinema Of Liberation In The Third World” in Film Manifestoes and Global Cinema Cultures. A Critical Anthology, ed. Scott MacKenzie, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2014, pp 230-250, p. 234.

25See Iotfi Maherzi, Le cinéma algérien, op. cit., pp. 38.

26Quoted by El Kenz, L’odyssée des cinémathèques, op. cit., p. 146.

27Ex. “La nuit a peur du soleil” (“The Night is Afraid of the Sun”, Mustapha Badie, 1965), “Le vent des Aurès” (“The Wind of the Aures”, Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina, 1966) “ L’opium et le bâton” (“The Opium and the Stick”, Achmed Rachedi, 1971), “Noua” (Abdelaziz Tolbi, 1972) “Zone interdit” (Ahmed Lallem, 1972), “Chronique des années de braise” (“Chronicle of the Years of Fire”, Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina, 1975).

28Maherzi, Le cinéma algérien, op. cit., p. 93.

29 Quoted in El Kenz, L’odyssée des cinémathèques, op. cit., p. 244.

30Tamzali, Une éducation algérienne, op. cit., 62.

31Ahmad Hocine quoted by Paul Balta, “Les records de la cinémathèque algérienne. ‘Tous les cinéastes africains sont passés chez nous’”, Le Monde, 11/09/1975, translation by the author.

32Simon, Algérie, les années pieds-rouges, op.cit., p. 206.

33Ahmed Bedjaoui, “Quand le cinéma scintillait dans la nuit” in Les années Boum, ed. Mohamed Kacimi, Chihab Editions, 2016, pp. 51-73, p. 69, translation by the author.

34Maherzi, Le cinéma algérien, op.cit., p. 384.

35 See, for instance, Tamzali, Une éducation algérienne, op. cit..

36Mohammed Harbi, « Postface à l’édition de 2002 » in Frantz Fanon, Les damnés de la terre, Paris, La Découverte, 2002, pp. 307-311, p. 307, translation by the author.

37Fredric Jameson “Future City” in New Left Review n°21, May-June 2003.

38In her installation Foreign Office (first shown in 2015 at Palais de Tokyo), Khalili looks back at the liberation movements present in Algiers during the 60s and 70s.

39Les rêves n’ont pas de titre, an installation in the French Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, focusing on cinematographic solidarity between France, Italy and Algeria in the 60s and 70s.

40Léopold Lambert, “Algerian Independence and Global Revolution 1962-2022. Introduction.” in The Funambulist n°42 : Algerian independence and global revolution 1962-2022, op. cit., pp. 26-31, p. 30.

41Walter Benjamin, On the concept of history, translated by Dennis Redmond, available online here: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/benjamin/1940/history.htm (accessed on February 23, 2024).