The following text is a conversation with Carlotta Cossutta. Philosopher and activist, professor of Political Philosophy at Università degli Studi di Milano, she’s a member of NON UNA DI MENO and is co-chair at Casa delle Donne of Milan; she published Digital Fissures. Bodies, Genders and Technologies (2018) and Domesticità. Lo spazio politico della casa nelle pensatrici statunitensi del XIX secolo (2023).

The conversation took place some time after Cossutta’s conference on Federici’s book, held during Stramonio Festival (Como, November 29th to December 1st, 2024).

EM: What struck me in Federici’s book was intersectionality: that is the way it shows and proves that to speak of class struggle one must speak of patriarchal oppression, that for a complete analysis of gendered violence it is essential to also look at colonialism, at modernity – in an ecological perspective, too. And that’s why she doesn’t cut any slack to science and philosophy.

This method interests me. You’re a teacher, I’m a student; inside school and academia it’s important to cross disciplines, not just to talk about intersectionality but to do it with an intersectional practice.

CC: It isn’t simple. You grasp a focal point, of Federici’s work too – and she was largely criticized for wanting to put together different discourses, because purists of every discipline, historians, philosophers, economists found in that very kind of discourse the flaws, and of course they did. What Federici does and what we too need to do in our disciplines is to question the processes that bring to an established truth. This, and we know this very well, is a key issue for philosophy, but here we’re asking: who can tell the truth,, when, under which conditions, and what shapes of truth are we willing to accept and recognize? This question, if taken seriously, really challenges the process of specialization that was produced among disciplines from a certain moment in history. And it is no coincidence that you mentioned modernity, because it is then that the need to categorize started to take action, on bodies – to separate man and woman, white and black, rich and poor – but also on territories, animals, plant species, and on knowledge too. The distinction that creates knowledges that are not worthy of that name and ones that are: this is the first barrier to making our practices intersectional: it is not about something that we need to add to our current knowledge, as it sometimes happens: “let’s add women to philosophy”, “let’s add postcolonial studies to philosophy”.The goal should instead be to look in retrospective, to ask ourselves which conditions made philosophy possible? To reflect on the foundations is a frightening process, because it means to lose one’s bearings, but it could be the only way to be more intersectional.

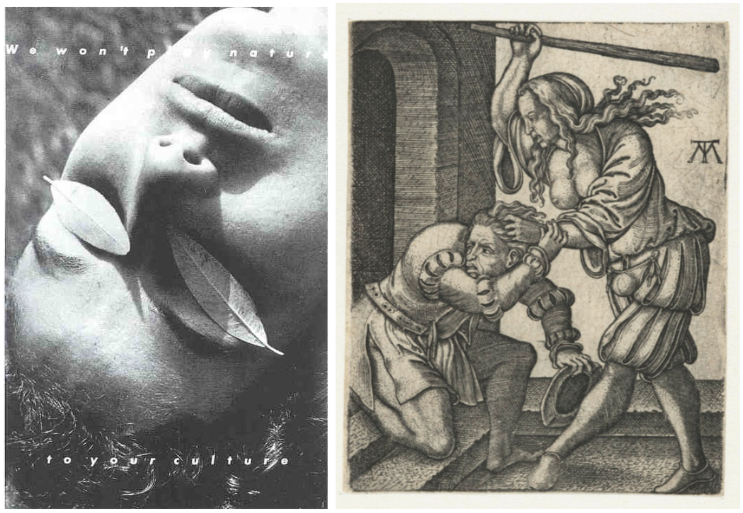

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (We Won’t Play Nature To Your Culture), 1983

Domineering wife beats husband with a stick, sec XVI

EM: Two weeks ago, at Stramonio Festival, you were talking about borders, not just metaphysical ones. I’m referring to the story of that organization helping women terminate pregnancies by bringing them in international waters [WoW]. Modernity didn’t only mean distinctions between disciplines but also brought the nation states, the enclosures…

Speaking of hybrid discourse, that teaches us to ask questions, to question texts – that could be written or made of images – I’m interested in talking about Federici’s book’s use of pictures, they not only accompany the text but have some agency, they are too the subject of her research. During the witch hunt images of rebel, domineering women and wives, with “insubordinate female tongue” that became afterwards those of a docile, tamed woman – to Shakespeare’s relief. It reminded me of Page duBois studies in Sowing the Body, about metaphors for the female body – from the great mother to a wax tablet. It seems that both texts speak to us in the words of aesthetic education; these are themes that still interest us materially, they did not go extinct in 2004, when Federici’s book was published. My question is on the power of images.

CC: Images have a huge power, and we often resort to interpreting them with the same canons that we use to read language, and they obviously are language, but they have another dimension. Or maybe two. Firstly there is the claim of universalization, because it is presumed that an image can be read by practically anyone. This has a positive aspect, since it makes us question the readability of other forms of transmission of knowledge, which often don’t have the same – assumed – immediacy. Moreover, we continue to think that this form of language is aside, or in some way primitive, to be surpassed by other kinds of knowledge processing. Museums always have info boxes that tell us what to see in every image.

The claim for universalization is also problematic because it hides the claim that there is a social imagery that we all share, that is the hegemonic imagery: images of the shrews becoming tamed. We find this repertoire with an unsettling frequency, and these images speak of the male gaze’s hegemony, and also of its assumed neutrality, because they are presented in a near scientific manner, as if they were simply the correct representation of what was happening and what had to follow. This ambivalence of pictures is, in my opinion, extremely productive – to read and to use. Propaganda always uses images; every text, every cultural object has an emotional resonance, but there is no doubt that images have a particularly immediate one, that is they often produce effects that are not mediated by the intellectual side – which is both good and bad – and this allows to think of them as an open field of possibilities.

EM: We’ve tried to toy with this in the last years: mediacy/immediacy, to learn to see and use images, to learn how to ask questions. While waiting I was reading Three Guineas –

CC: Another text with lots of images!

EM: Indeed. Apart from the layering of letters, I was struck by the issue of the war photographs. Woolf asks: shouldn’t they be immediate? Shouldn’t they immediately show why we should avoid war?

CC: Of course, it would be right, it would be immediate. Three Guineas is in the Political Philosophy curriculum because it holds great relevance. There are images that we think should provoke immediate horror and should make us feel that war is wrong, as is slaughtering people. In two ways we see that this is not the case: for example, the Gaza genocide constantly presents us with images of massacres, on every channel – from social media to news outlets – and they don’t spark the will to mobilize, and instead create a kind of tolerance, they become background noise. On the other hand we see even more polarization: some months ago it was common to hear people say that the images of palestinian deaths were fabricated. The very images that were supposed to jolt us makes us doubt their veracity, confirming what we were thinking in the first place. A second element, if we think about campaigns against violence against women, they are almost exclusively directed at women, and they always depict women as victims. The most common – with different variants – is a picture of a huge male fist that comes out of nothing against a scared, hurt woman. This obviously wants to horrify, I believe the actual effect is on one hand to make men feel entirely not implicated in that discourse – “that fist is not me” – and on the other to reiterate the image of the tamed, docile woman, also confirming the idea that kinds of violence that don’t look like that don’t count (psychological, economic violence), in short, no one feels rightfully represented.

EM: Do we want to start talking about representation? Once again from modernity on…

CC: Yes, but the kind of woman that gets represented is also relevant. It is impossible, even when we’re enduring violence, to be outside of the beauty standards. This too signals exclusion lines: if you aren’t like that woman we don’t care, you can suffer violence.

EM: Speaking of themes close to us, most of the book wants to prove the burning historical relevance of reproductive rights – and I appreciate this materialistic motif in Federici, who after all is a marxist – that introduces the character of Caliban, the body, since, as Cavarero brilliantly showed, women, matter and the body are tied since Plato’s era. Caliban is the (not exclusively female) body that gets put to work, exploited.

Giotto, Wrath, 1306 Ana Mendieta, Untitled: Siluetas series, 1970s

CC: The theme of bodies put to work that lose freedom in the process is present, and it moves along the lines of others’ inferiorization, that happens in different spheres but along the same lines – this is interesting in Federici’s work: slaves, colonized peoples, factory workers and miners share the same destiny of not being considered able to decide for themselves. This relates to the productive question, but if we look at the Italian law on abortion, nr. 194, the text reads that if a person decides to terminate a pregnancy, they should be given an ulterior seven days, to reflect on it. Apart from being a huge practical problem, a real inconvenience, apart from the material side here the symbolic one is relevant because it means that the decision that you took on your own isn’t enough, you didn’t think about it well enough – “go home and think about it some more”. The same infantilization process is perpetrated against colonized people. In Italy we have a long history that we tend to unsee with the inferiorization of colonized populations. The goal – expressed by every politicians from the formation of Italy to the fall of fascism – was to allow us to have a better opinion of us as italians. Let’s think of a character like Indro Montanelli and the famous interview in which he talks about the Eritrean child he bought – even if he used to say ‘married’ – in which he defines her as a bestiolina (pet, small beast), common racis topos, to define others as closer to animals than us, but also says that “at that age they are already women”. We’re talking about thinking other bodies as radically different from ours, so much that even if that is a 12 year old’s body, they are already women. This brings us to another central theme for Federici: also in the Women category we have lines of diversity and exclusion, it is different to be a white middle class woman (daughter of an educated man) and to be an enslaved woman, for example.

EM: The same material relevance belongs to the importance and consequent targeting of indigenous women, that according to Federici were “the heart of the community” and therefore the heart of resistance.

CC: On this topic we can read Federici together with other authors. Let’s consider bell hooks’ on the home as a space of resistance, where subjects that seem like the most oppressed, the most marginal, black women, keep the hope for resistance alive in those very spaces judged to be politically irrelevant, using firstly reproductive labour, also believed to be irrelevant – for example, bell hooks takes issue with Frederick Douglass, champion of the ‘800s anti-slavery movement, who used to say he never had a good relationship with his mother, as she was working in another plantation. She points out that this belittles the effort his mum probably made to walk to him every evening if only to watch him sleep and then to walk back and work the next morning. It is clear that they didn’t have a perfect mother-son relationship, but there was the attempt to be, precisely, the heart of the community and therefore the heart of resistance.

EM: It reminded me of Baby Sugg’s memories in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, that shows the grandmother being an important figure in the liberated slaves’ community and then the two women get shunned. Then the difference already struck, sexual difference I mean.

CC: About this, Federici’s work is important because it imposes a new relationship with the past: we can reread History to save from oblivion all those stories of resistance or alternative forms of life, which doesn’t mean forgetting that they may have been defeated – as you were saying, sexual difference intervenes – but we can use them to build alternative genealogies. Let us say that, of course, there was modernity, but inside of it there were forms of resistance from which we can evidently learn something.

EM: Indeed, allow me this question, what can we learn from the struggles depicted in the book and, layering, those of the Sixties and Seventies (Federici’s work is from 2004 but her activism started way back in those crucial years)? Can we get something back, without being nostalgic?

CC: You already got the first thing: a materialist approach that doesn’t need to be orthodox but forces us to look critically at real life conditions, how we use our time, at the global care chains and therefore at the oppressive relationship that we too establish with other women. To look at the material conditions means to push outside the cultural perspective that is liable to erase differences among women and at the same time to overlook some of the most pressing issues – that often aren’t what we want them to be, or what we represent them to be.

The other element is the weaving of community – a theme on which Federici insists, also through the attention to the commons, or the struggles in South America that deal with ecological issues presenting a non proprietary alternative, these are struggles that go beyond the nation states’ borders. Weaving community also means to build places of confrontation and relation in which there’s space for diversity and conflict. These were the consciousness-raising groups that Federici frequented. They were spaces where we didn’t expect to be all on the same page, we were creating non homogeneous communities. In a world that moves more and more towards individualization or the formation of very homogeneous bubbles, we must go back to thinking we can sustain common struggles and work together even if we are very different. This teaching helps us to avoid flattening all stories on ours or on the ones we know best, the ones we like to narrate.

EM: Reading the book you get the feeling that there was really only one struggle, to which different subjectivities contributed differently, in different fields.

CC: This is another element that urges us to think, regarding feminism for example – I talk about this because it’s one the grounds I know best – in recent years we’ve often approached it as if there were sectors. But women are everywhere; fighting for women’s rights doesn’t mean to forget the working class struggles: women are workers, women are migrants, and not only that – that’s the point. Shining a light on differences shouldn’t mean dividing the struggle, it is about bringing a new point of view, a new method, a new, not separated aspect.

EM: You speak of recent years; for someone born in 2005 getting familiar with resistance stories, but also to the artistic practices of Federici’s years – I’m thinking of those works from Martha Rosler, Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman – it makes you think there was something entirely different in the air, that the world was radically something else. Makes you wonder what was the decisive change, was it really “that damn phone”?

It could sound banal but I’m thinking of isolation used as a weapon, and to fear – which is ironic, given that the Enlightenment and Hobbes’ goal was to free us from fear, or perhaps to free men from fear – from the climate of terror and suspicion of the witch hunt to post fordism (often characterized as a feminization of labour), to the digital era. Duby would maybe say that we don’t live elbow to elbow anymore, like in medieval society, even if that was also slightly suffocating.

CC: I wouldn’t say “that damn phone” so much as, once again, that damn capitalism and the logic controlling that damn phone. If we look at the dawn of the Internet, it had a deeply transformative potential, just like many technical innovations. Some feminist collectives, like VNS Matrix, were working to ensure that the situation of not being elbow to elbow could bring rebellion spaces and again put something in common. The dream was that knowledge would finally be widespread, freely accessible to everyone, and this partially persists in those bubbles that are formed today. Proprietary and consumption logics won, making it so that in the phone our identity is in service of profit and therefore constantly simplified. On one hand the emphasis on authenticity, but only in ways that the algorithms can recognize. This produces a skewed idea of community, not being elbow to elbow becomes only being with who we are similar to, but also encourages us to think that communication practices can be sufficient to transform material conditions. Even though they can be extremely powerful, we shouldn’t believe they are necessarily enough.

EM: As we were discussing two weeks ago, the restoration of striking as a diffused practice, which is not only provenly effective, but also fertile inspiration for new resistance methods. I think in the discussion we were referencing mostly traditional forms of strike, refusal of labor, but recently the South Korean 4B Movement (no dates, no sex, no children and no marriages with men) also gained popularity, and that is about the refusal of emotional and reproductive labor.

CC: Exactly, it’s a form of subtraction. And not such a new one, if we think of the ancient comedy, Lysistrata, who convinces women to join a sex strike to force men to stop wars, that’s what we’re talking about. What connects the two types of strike? Time. Being able to take back time and also be able to have an effect on someone else. And this someone could be men, employers, social media. This is against a certain modern conception of time that requires us to always be available, requires every moment to be productive.

EM: To go back to Three Guineas, isn’t this the type of indirect influence that Woolf excludes at the beginning of the book, saying that it is undignified and not enough?

CC: You haven’t finished the book yet, have you? I’m not going to spoil the ending for you, but yes, in a way it is that kind of influence, but the point is not really exerting influence but taking back one’s own time and subjectivity. The influence dynamic is present but only as a side effect.

EM: Now I’m even more curious about the ending! But, to end this conversation, I want to ask you, since you have a privileged viewpoint being a part of them everyday, about nowadays’ feminist collectives and how they operate: do they manage to create those divergence spaces? The different approaches to feminism are able to find common grounds to meet on? Can they be combined, can they not be combined but it’s okay and it’s better to place them side by side and create alliances?

CC: Complex question. The starting point is that we have feminisms, plural. This is good, feminism also is a battlefield, discussing within feminism is useful and we’re at a point where there is a sufficiently long history to have shed light on some perspectives. Some of these are clearly incompatible: is it obvious that Federici’s stance and the perspective of Sheryl Sandberg, author of Lean in, have few common ground. Without having to decide that one of them can’t call themself a feminist, but we need to know that different forms of feminism exist and to say which one we’re referring to when we talk about it – I say this also in response to some critics often presented to the movement.

Perhaps this was the point of your question: do we have community today? I remain optimistic and say we do, but what’s the difficulty? Those very social transformations, the fact that we live in a world that makes it hard to imagine alternatives, utopias, a world in which mechanisms of socializing towards political practice are lost, to build these political subjectivation processes is an ulterior task of weaving communities. This is nonetheless a precious possibility: we are not meeting on the basis of an established constituent idea or an ideological stance, but building on a desire, a necessity, to get new tools. Naturally, this slows down the pace of political action, and we risk many conflicts, but this is one of the challenges of contemporary feminism: to create community and kin even with people that have never taken an interest in politics, without thinking that you have some kind of right stage that you need to reach to speak up, and instead you can do it starting from your everyday experience. Of course, that implies more effort.

EM: The process is important. That’s why art is crucial, and it doesn’t live outside of reality. Attention to the medium, to materiality – body, matter, kinship with the world – and to the process, the act of making something new, to cite Arendt.

CC: Exactly, we’re talking about the possibility of beginning something new, building political spaces that aren’t limited to dealing with the materiality of present things but try to add something more.

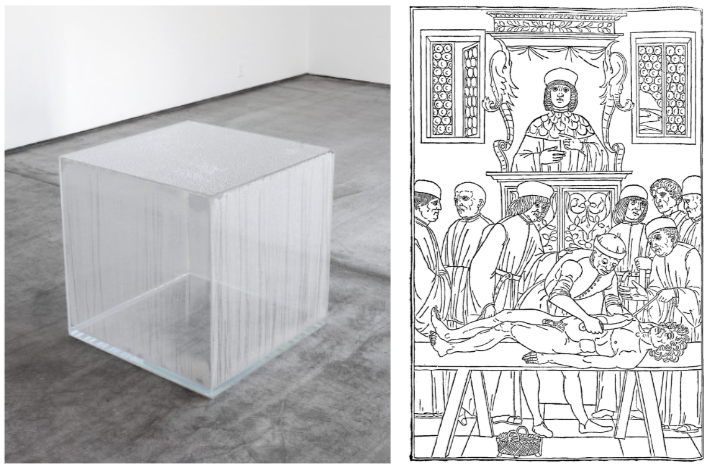

This has lots to do with art because you always need to deal with a material given, an other that has its own agency. A sculptor is free to choose between wood or marble, but they can’t control the material’s qualities. It has also something to do with the ability to imagine something different.

Hans Haacke, Condensation Cube, 1963-67

Johannes de Ketham, from Fasiculo de Medicina, 1495

EM: These are the stakes of teaching: to guide to see, to read images.

CC: Inside and out of art the role of teaching is to create a method to stay with reality, it can be reading text in a philosophical or aesthetic way, it can be to cross the methods, but it’s always about offering an interpretative grid. It is not a matter of deciding which language is the truest or the best, but understanding where it is positioned, reading the context.

EM: Positionings, once again we call back to the Seventies.

CC: Of course, positionings, that must be recognized and then crossed over, questioned.

Elisa Mancioli

Carlotta Cossutta