This was a horrible film and the last one which I was forced to make against my better judgment.

—George Cukor

All I can remember about that one is that I hated it… It was terrible.

—George Cukor

Directors are not always the best judges of their films. Hitchcock, for example, always measured the success of his movies by how well they did at the box-office. So he always pooh-poohed masterpieces like Rope (1948) and Under Capricorn (1949), both box-office failures. But with A Life of Her Own (1950), critics and audiences and even historians agreed with Cukor, the director of the film. Even now, sixty years later, Cukor’s biographers also concur. No biography bothers spending more than a few paragraphs complaining about how bad the movie is before moving on. All the griping notwithstanding, it is a minor masterpiece, maybe even more than that—a John the Baptist, if you will—pointing the way to Cukor’s future cinemascope masterpieces like Bhowani Junction (1956), Les Girls (1957), A Star is Born (1954), and the VistaVision Heller in Pink Tights (1960).*

Although the script is certainly more interesting and intelligent than Cukor said it was, it’s not a movie that we watch because of the originality of the story. It’s a fairly straightforward cautionary tale about a young woman (Lana Turner) from a small town who comes to New York to be a fashion model. She succeeds beyond her wildest dreams but doesn’t find happiness until she meets a man she falls in love with (Ray Milland). It turns out that he is married, but for a variety of very good reasons, can’t leave his wife. Perhaps the problem with the reception to the picture was a result of bad timing. That field had been plowed many times in the 30s and 40s. After the end of World War II, there was clearly a sea change in what audiences seemed to want. The decline in popularity of “women’s films” in the late 40s, as well as the aging of its foremost proponents, like Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, and Barbara Stanwyck, signaled at least a temporary death knell for this subgenre. The lack of interest in and the condescension shown to films of this sort, even to this day, might go a long way toward explaining why the much-underappreciated Daisy Kenyon (1947) by Preminger, No Man of Her Own (1950) by Mitchell Leisen, and A Life of Her Own were ignored and are only now, hopefully, being re-discovered. Max Ophuls’ American films of the same period, women’s magazine fictions like The Reckless Moment (1949), Caught (1949), and Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948)—most decidedly not a magazine fiction—did not fare much better with the public or the critics, at least not in the United States. But the respect for Ophuls and his re-emergence in France as a major director in the early 50s and their frequent appearances on television kept those films from falling into the black hole of oblivion.

This kind of melodrama would be reinvented in the 50s with the addition of wide screen, color, and newer and younger stars—Jane Wyman, Susan Hayward and, of course, Lana Turner. But, for the most part, full-throttle melodramas would be more about families and intergenerational conflicts (East of Eden [1955], Giant [1956], Written on the Wind [1956]), often based on doorstop-sized, best-selling novels, and would deal with groups of people (The Cobweb [1955], Peyton Place [1957], The Best of Everything [1959]) rather than one woman—the star, of course—and her difficulties in choosing between love and a career.

In the old days of cinephilia—long before the Age of Spielberg, the Avid, and CGI—a director’s skill and expertise would be judged on his abilities to stage a scene within the frame and how well he succeeded at it. In the 40s and 50s, when dollies became more prevalent as a result of less cumbersome cameras and more flexible lighting was possible, the dolly shot became an integral part of the vocabulary of filmmakers everywhere (think Ophuls and Mizoguchi), and especially in Hollywood. Masters like Hitchcock, Welles, Preminger, and Minnelli would often try to do a whole scene in one sinuous take. It was the master filmmaker who would cram as much information as he could into the frame, while moving the camera and permitting the action to unfold in real time rather than cutting it into little pieces in the traditional Hollywood iron maiden of master, medium shot, close-up, shot/reverse shot.

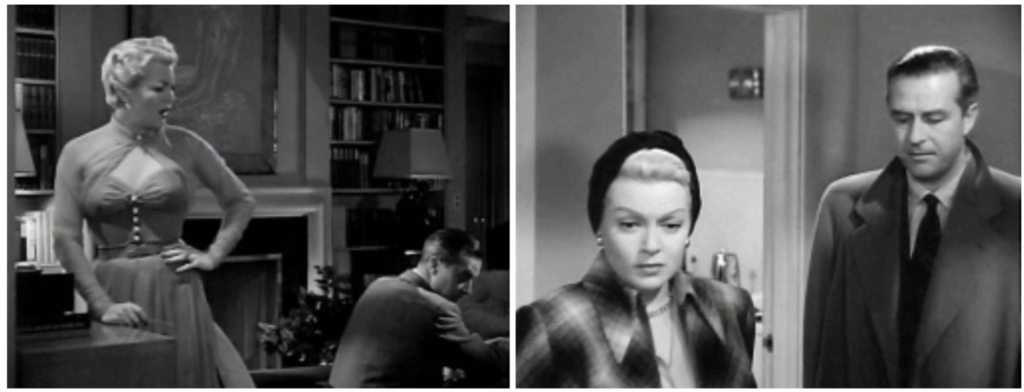

In A Life of Her Own, many scenes are played as a single take. The movie is practically devoid of close-ups. When there are two actors in the scene, they are not isolated from each other by cuts but appear together as we see them both as well as their reactions to one another at the same time. They are positioned almost at the edge of the frame, one of them partially out of the frame, as if they are prepared to burst out of the artificial borders that confine them, as if they are planning an escape. They are never isolated in close-ups divorced from their environments. We always see clearly what is behind them, and the framing exudes a tension that makes us want to see more—to see what is beyond the frame, on either side of the characters. The framing almost begs us, in our own imaginations, to expand the screen to a wider screen format so that we can place the actors more firmly in the environment they inhabit.

Turner with Barry Sullivan Turner with Tom Ewell

Turner with Milland

Even in Cukor’s framing of the actors, Cukor himself seems to be looking forward to the day when we can see even more of the set-decorated landscape in which his actors live out their lives. In short, he is anticipating cinemascope and wide screen in the way he directs the movie, just as Minnelli was in the ballroom scene in Madame Bovary (1949), Lana Turner’s crack-up-while-driving scene in The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), and practically every musical number he directed before Brigadoon (1954), his first cinemascope film.

The directors of the 40s who were most successful in making films where sensuous tracking shots followed the actors and permitted them to interact with each other in uninterrupted takes—directors like Hitchcock, Minnelli, Preminger, Sirk, and Cukor—were among the directors who, with the arrival of cinemascope and wide screen, were able to make their crowning achievements in the new format. By realizing the potential of the format, they created masterpieces that they were not even aware they could achieve previously—although, as I am suggesting, they sensed that something was missing in the confining formats that were available. The new wide screen technology freed them in ways they never could have dreamt of (just as Hitchcock and Renoir were able to achieve unimagined glories with the addition of color to their toolboxes as filmmakers). A Life of Her Own, a gorgeous black and white film, is fine just the way it is. Preminger, Minnelli and Cukor were waiting, if only on an unconscious level, for cinemascope to free them from the frames that could no longer contain their visions. But if A Life of Her Own transcends the “women’s picture” genre, it is because of the formal values which today look as fresh as ever.

This is just surmise on my part—but if one looks at the scene of Lana Turner leaving Ray Milland at the airport as she descends the ramp into darkness, dodging in and out of pools of shadow and light, as if fleeing from the scene of the crime, can one not imagine that this was the inspiration for Jean-Pierre Melville in the breathtaking opening shot of Le Doulos (1962)? Or the empty apartment Milland and Turner rent, which includes open spaces in which people appear and reappear from hallways, doors and around corners—did this influence Godard, knowing how he devoured everything and forgot nothing, in the middle section of Contempt (1963)?

Serge Reggiani in Melville’s Le Doulos (1962)

Brigitte Bardot and Michel Piccoli in Godard’s Le Mépris (1963)

I don’t bring up this point to ennoble or add prestige to an undeserving film—but only to suggest that even though the mechanics of the plot may hark back to the past, in terms of formal strategies and the way it looks, it points towards the future and suggests new cinematic approaches to commercial narrative cinema. Just as a point of reference, the film was made in the same year as Antonioni’s Cronaca di un Amore, which similarly explores the possibilities of film language while grounding itself firmly, on the narrative level, in genre conventions. While Antonioni’s film was hailed and recognized as a landmark in modernism, A Life of Her Own, possibly because it was a Hollywood “product” was, and still is, casually dismissed as a retrograde look backwards, a victim of its plot.

Which is not to say that all its beauties are available only to cinephiles with a long memory. Despite Cukor’s claims to the contrary, the script is very good, and Lana Turner, under Cukor’s direction, delivers one of the most natural, relaxed performances of her career. She is no longer the brittle, porcelain beauty who has difficulty in suggesting an inner life or intelligence or wit. Similarly all the other characters are well rounded, well-written and performed. Margaret Phillips, a New York stage actress who was to become a fixture of live television drama in the 50s, gives an especially graceful performance as the wife we (and Lana Turner) would like to hate, but can’t. And then, for Cukorphiles (well, who else would be reading this?), we have yet another example of the pull between the life of artifice—in this case, modeling—, the life on stage, or in the movies, the faces we present to each other in society, when our masks are firmly fixed in place, versus the lives we live when we are deprived of these delicious crutches.

Guess which one Cukor prefers?

Mark Rappaport

April 2012

*I am indebted to Bernard Eisenschitz, who saw the movie due to my enthusiastic recommendation, for the aperçu that A Life of Her Own is a cinemascope manqué movie—a cinemascope film avant la lettre.