A star-driven, crime caper, the Hong Kong-China co-production Project Gutenberg (2018), by writer-director Felix Chong, was a box-office success across the People’s Republic of China (PRC) upon its release in 2018. Indeed, according to Boxofficemojo it was the 14th highest grossing film in the PRC in 2018. With a cast that included reliable box-office attractions Chow Yun-fat and Aaron Kwok, in many ways Project Gutenberg can be seen as typical of the sort of films that appeal to Chinese Mainland audiences. Slightly less typical for films popular in Mainland China was the manner in which the makers of Project Gutenberg actively celebrated the history of Hong Kong cinema. In particular, through its visual style, use of genre, and creation of character, the film clearly evokes cinematic elements that are emblematic of the local and international success enjoyed by Hong Kong films, such as A Better Tomorrow (John Woo, 1986), in the 1980s and 1990s.

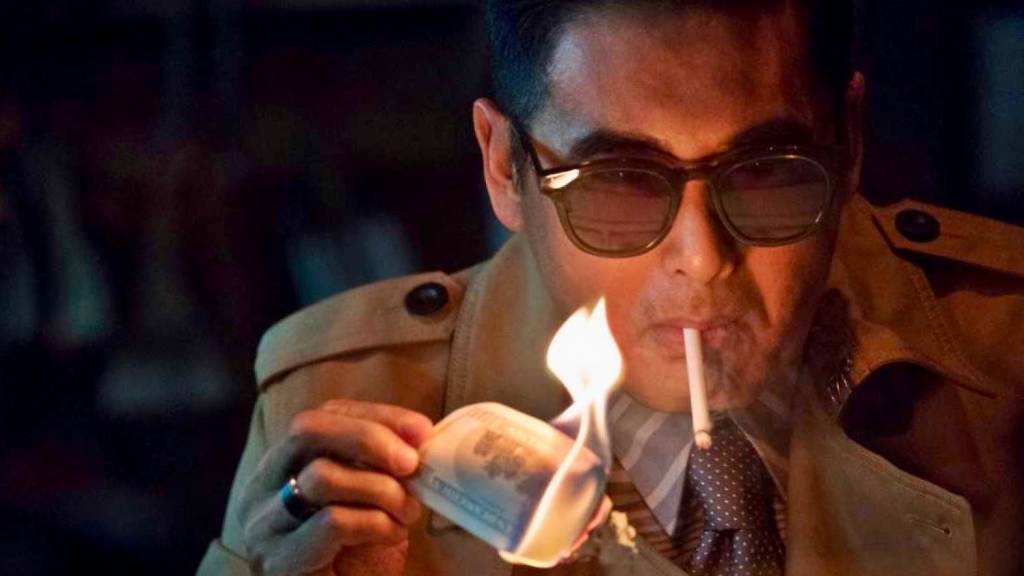

Figures 1 and 2.Project Gutenburg (top) clearly references A Better Tomorrowfrom 1986 (below).

It is through the manner in which Project Gutenberg acknowledges its own status as a piece of Hong Kong cinema, particularly through its various references to other Hong Kong films, genres and performers, that it can be seen as part of a wider trend within contemporary Hong Kong film production that offers a perceptible level of self-reflexivity. In doing so, films such as Project Gutenberg evoke specific aspects of Hong Kong’s cinematic traditions. Such elements could be dismissed as an example of a cinema that has declined to the point where it has become so short of new ideas that it has turned in on itself in an instance of reductive self-parody. However, in order to counter this argument in this article I want to explore how this self-referential impetus can also be read as a way of asserting the idea of a distinctive Hong Kong cinema, and by extension of Hong Kong itself, in the face of ever more pervasive co-productions with Mainland China, designed to appeal to audiences there rather than in Hong Kong. And how, in doing so, the self-reflexive tendency within Hong Kong cinema, in effect, offers an engagement with contemporary politics in the region at a time of growing resistance in Hong Kong against the influence of Mainland China.

In the case of Chong’s Project Gutenberg, it is a celebration of the “golden age” of Hong Kong film production in the 1980s that is undoubtedly a clear touchstone. That was an era when Hong Kong production was at an all-time high and its films were finding markets across the world having previously circulated mainly in Asia and to diaspora communities (Bordwell 115). This was also an era when Hong Kong cinema was dominated by Cantonese language productions, having previously made films in both Cantonese and Mandarin (Bordwell 3). In Chong’s film, the appearance of Chow Yun-fat, an iconic performer from that era, in one of the lead roles, along with the use of action choreography that explicitly references the actor’s work with director John Woo in films such as the aforementioned A Better Tomorrow (1986) and The Killer (1989), draws the audience’s attention backwards to that era when Hong Kong films and filmmakers were key contributors to world cinema.

The nostalgia for this period of Hong Kong film success so clearly present in Project Gutenberg is palpable from the outset. As I shall explore further in this article, in recent times Felix Chong was not alone in evoking a sense of longing for past cycles of Hong Kong production in his work. A number of other filmmakers have also revisited Hong Kong’s cinematic past in a variety of ways, drawing on recognisable aspects of film production in the city in a manner that can be read as in some way political. It would of course be possible to simply dismiss this backward-looking set of references to a cinematic past as empty exercises in nostalgia along the lines that Fredric Jameson famously did when discussing pastiche, arguing that: “In a world in which stylistic innovation is no longer possible, all that is left is to imitate dead styles, to speak through the masks and with the voices of the styles in the imaginary museum” (7).

However, given the very particular industrial and political contexts of Hong Kong filmmaking in the 21st century, the nostalgic evocation of the past in recent Hong Kong cinema can be read as much more than a simple exercise in nostalgia. The recent politics of Hong Kong, particularly in terms of its relationship with the government of the People’s Republic of China, can be read through the self-reflexivity that runs through these recent Hong Kong films. In particular, this self-reflexivity which, as noted, often recalls the cinematic past of the territory, also importantly evokes a moment when Hong Kong films were clearly distinguishable, in terms of both form and content, from the products of other film industries.

This article considers the ways in which this self-conscious and highly reflexive evocation of past eras of production, popular genres and filmmaking styles within recent Hong Kong cinema can be read politically within the context of contemporary political struggles within the territory. In order to explore this recent self-reflexive cycle of films, I will begin by discussing critical responses to work that is emblematic of this trend. First, through critical reaction to the film Gallants (2010), which were often framed through the writing of Ackbar Abbas, and his concept of Hong Kong as a “space of disappearance” (1). This will be followed by a discussion of the 2016 crime film Mobfathers (Herman Yau, 2016), which as I shall argue can in many ways be seen as typical of this trend. The focus will then turn to the horror genre by focussing on two films, Rigor Mortis (Juno Mak, 2013) and The Sleep Curse (Herman Yau, 2017), which also display wide-ranging references to Hong Kong’s cinematic past. Horror is a genre that is not widely produced or distributed in the People’s Republic of China, often due to the authorities being suspicious of films that involve elements that can be labelled supernatural, and I will argue that the self-reflexivity within these Hong Kong produced works is often linked to ideas of their representing a “new localism” that offers Hong Kong audiences “a sense of recognition and empowerment” (Teh 1). This particularly occurs through the films’ evocation of genres and styles of filmmaking closely associated with the Hong Kong film industry. In addition, this evocation of Hong Kong’s cinematic past within both the form and content of films such as Gallants, The Mobfathers,Rigor Mortis, and The Sleep Curse within can be read politically in the context of a historical moment when the relationship between Hong Kong and the People’s Republic of China, generally after the handover on 1st July 1997, but more particularly after the Umbrella Movement of 2014, has often been strained and fractious.

Ackbar Abbas and the Idea of Hong Kong’s “Disappearance”

In one of the most influential pieces of writing about culture and Hong Kong, Ackbar Abbas refers to the territory as a “space of disappearance” (1). It is of course significant that he was writing as Hong Kong moved towards handover back to the People’s Republic of China in 1997. Abbas argues that “Cultural forms…can perhaps…be regarded as a rebus that projects a city’s desires and fears” (1). He goes on to articulate an argument for Hong Kong’s difference from Mainland China, one that posits the idea that the city and its inhabitants are not simply or essentially “Chinese.” Here he clearly demarcates a sense of difference between the People’s Republic of China and Hong Kong. Film offers an important way to explore this difference.

Cinema’s place within Hong Kong’s cultural landscape is therefore highly significant in this regard. The international success of its film industry and the fact that films produced there have been an important export, as well as their position as a vehicle for delivering Hong Kong’s image abroad, is also extremely relevant, and contributes to it being a historically important aspect of Hong Kong’s identity (Teo vii-xi). Abbas links this to the historical changes he explores in Hong Kong when he states that film “is the most developed and popular of Hong Kong’s cultural forms”, and that as such, “cinema has such a privileged position in Hong Kong’s culture of disappearance” (17).

Since Abbas asserted the importance of films and film production to Hong Kong’s cultural identity, the industry has gone through a significant period of decline. The Asian financial crisis that occurred around the time of the handover in the late 1990s may have been part of the reason for this, as well as a decline in markets for Hong Kong films abroad, as regional competitors such as South Korea saw a rise in local production and international critical acclaim for their films at prestigious film festivals. In addition, there was a notable change in local audience tastes that saw them choosing Hollywood blockbusters over Hong Kong productions (Teo vii). Whatever the combination of these factors, the annual number of films produced by the Hong Kong film industry has plummeted from a high of 200-300 films in the 1990s (Celine Ge writing for the South China Morning Post has gone so far as to suggest it was as many as 400 films a year) to a meagre annual total of 50+ more recently, with the total output being 53 in 2018. Through this decline in film production there is a clear and on-going physical disappearance of Hong Kong cinema. In addition, this has also resulted in the evaporation of films that directly address or reflect the experiences, real and imagined, of Hongkongers. The lack of reflection of, or engagement with, local concerns may also explain why a number of the high profile Hong Kong-China co-productions that are hugely successful in Mainland China do not find as receptive an audience in Hong Kong. As Liz Shackleton, writing in ScreenDaily, notes, “Hong Kong audiences are resistant to films with a strong mainland flavour.” It would seem therefore that audience trends suggest that Hong Kong audiences, while they will embrace products from Hollywood are still not open to films that reflect the experiences of Mainland China.

As this tendency in Hong Kong audiences has continued, it has been possible to discern a trend in local production that has attempted to lace films with references to the specificity of Hong Kong, reflecting the concerns of its people, and its places and spaces. A good example of this is Amos Why’s 2014 film Dot to Dot, which follows a Mainland language teacher who notices a series of visual puzzles on the walls near MTR stations. As she attempts to solve them, her investigations lead her to find out more about Hong Kong’s distinct history, architecture and identity. Alongside the physical spaces of an older Hong Kong, Dot to Dot utilises archival photography to assist its nostalgic representation of the city’s geographical past. As Yvonne Teh noted in her review of the film for the South China Morning Post, “local references will surely inspire Hongkongers to reminisce about places that were once part of the city’s physical and cultural landscape.” Whilst in terms of its form Dot to Dotdoes not display the same level of self-reflexivity of other films I will now turn to, it does show how widely nostalgia can be identified as a significant drive that has informed cinematic practice. Here, primarily in terms of the choices of location and settings, but also in the casting of Shaw Brothers star Susan Yam-Yam Shaw in a small but significant role as the Head of the language school.

It is significant that, amongst the films that offer an engagement with Hong Kong’s cultural identity, a strong element of nostalgia exists. In a certain number of examples, perhaps unsurprisingly given Abbas’s assertion of the centrality of cinema to this idea of cultural identity, this revolves around Hong Kong’s very particular film history. As I shall explore below, this results in films that include a plethora of references to particular films, genres and stars, and by extension a local cinema that existed before the Sino-British declaration of 1984 that set up the handover and its subsequent delivery in 1997. In these nostalgia films, there is a suggestion that whilst this was a time when Hong Kong was a British colony, at least in terms of cinema it enjoyed some level of independence and a clear local identity.

Nostalgia in the Context of Hong Kong Filmmaking

Given the contemporary political situation in Hong Kong, nostalgia for a time when the city’s film industry and productions were a source of local pride can be clearly related to on-going politics. In particular, a cultural politics that is linked to the wider struggles that are taking place both in the spaces of Hong Kong as well as on screen in an imagined Hong Kong. The manifestation of these struggles within recent films may be seen as in some ways being about Hong Kong’s identity, and in some instances they are citing a contested past in an attempt to delineate a possible future.

The endeavour to create or save a memory of Hong Kong is discussed by Yiu-Wai Chu when he explores the cultural politics of a season of 1980s films held at the Foo Tak Building in Wan Chai on Hong Kong Island in 2009 called “Reclaiming the Past That Belongs to Us: Not for Nostalgia.” He states that “[t]he series showcased a number of Hong Kong films from the 1980s, inviting the audience to reflect on the possibility of an alternative Hong Kong. […] to remind the audience of what Hong Kong cinema had once achieved” (165). This is a reflection of a past cinema that is specifically one of Hong Kong and one that at the same time was manifesting itself in the self-reflexivity found in films made by younger filmmakers, who themselves are harking back to the territory’s cinematic past. It is within this trend in production that one can begin to identify in the context of Hong Kong cinema a rising politics of self-reflexivity. Thus, in an era that has seen growing political moves to to erase an identifiable, and arguably unique, Hong Kong identity, the celebration of Hong Kong’s particular cinematic past becomes in itself a political act, one that re-asserts through the example of film the distinctive nature of the city and territory. This, in turn, offers the potential for films from the past that when first released may not have had explicit political intentions become in this new context works of potential radical significance.

Gallantsand The Mobfathers: Countering Disappearance

Ruby Cheung has noted that the self-reflexive aspects within recent Hong Kong productions can be seen as a form of “collective memory” (105). It is this evocation of collective memory that suggests that audiences are invited to experience or read these “new” films through the lens of local film history and potentially as part of a continuum. Therefore, by activating this collective memory through cinematic images, these films may also be read as conscious or unconscious attempts to counter the “disappearance” that Abbas associates with the post-1997 period in Hong Kong. Gallants, a 2010 low budget Kung-fu film, directed by Clement Cheng and Derek Kwok, brings these things together through its references to Hong Kong’s cinematic past. For Cheung, the directors do this by “re-visiting the kung fu film genre, which includes the use of specific cast and other stylistic elements” (134).

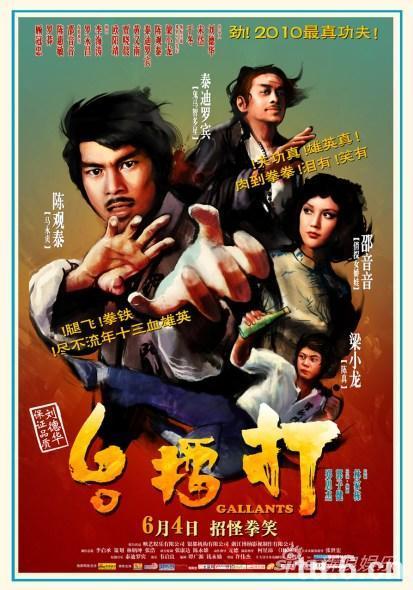

Figure 3. Poster for the release of Gallants evokes those of the 1970s.

The casting of the film is certainly knowing and is in many ways key to the nostalgia present. A number of the actors cast in the film have distinguished careers in Hong Kong cinema, and particularly within Hong Kong martial arts films. Leung Siu-lung, an actor associated with a number of Bruce Lee-style films from the late 1970s and 1980s, plays Dragon. Chen Kuan-tai, a major star of the 1970s and early 1980s, plays Tiger. Both performers were associated with the Shaw Brothers’ studio and their style of kung-fu cinema. Gallants’ key setting of the teahouse directly evokes the 1974 Shaw Brothers’ hit film The Teahouse directed by Kuei Chih-Hung and starring Chen Kuan-tai as Big Brother Cheng. In that film, as in Gallants,the teahouse is a space of resistance—a place where a, somewhat idyllic, community comes together to resist outside forces. In the 1974 film, this threat was represented by juvenile gangs threatening the cohesion of local communities, in Gallants it is gangs working for unscrupulous land developers hoping to exploit the teahouse location for redevelopment, and in doing so remove the areas links to the past. In both instances, the threat seems to personify a modernisation that in some way seems to have the potential to disrupt the communities link to the locale and with that a continuity to its past.

Reflecting how well received its nostalgic tone was in the territory, at the 30th Hong Kong Film Awards (2011), Gallants won the Best Film award. Another film that drew on a similar sense of nostalgia, this time for the Hong Kong crime film, and in particular the very popular triad cycles that were a staple of Hong Kong cinema at various points across the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, was The Mobfathers (Herman Yau, 2016).

The Mobfathers is a film that self-consciously utilises the codes and conventions of the triad film, a form closely associated with the cinema of Hong Kong. A local form of gangster film, cycles of the triad film have been successful at the Hong Kong box-office at various historical moments in the wake of the release of works that proved to be popular successes (Bordwell 26-27). For example, in the mid-1990s, there was a revival in the popularity of the triad film following the release of Young and Dangerous (Andrew Lau, 1996), which proved so successful it spawned five direct sequels and a number of related films that used characters or situations that were drawn directly from the series, such as Once Upon a Time in Triad Society (Cha Chuen-yee, 1996). Often at the core of these films is the violent rise to the top of a lower-ranked young gangster, who across the film’s story battles to become the leader of the triad and in doing so sweeps aside the elder generation of gang members.

Figure 4. Poster for The Mobfathers.

Aware of the triad film’s lengthy popularity at the Hong Kong box-office, and of its status as a particularly Hong Kong-based take on the gangster film genre, the makers of The Mobfathers offer a high level of self-reflexivity in order to make a comment about Hong Kong and its relationship with The People’s Republic of China. There is even an exchange between gang member Luke and his daughter when they discuss the fidelity of Hong Kong’s cinematic representation of triads. She asks, “Which film is closer to real life? Young and Dangerous, Election or Laughing Gor-Turning Point?” Such cinematic references invite the audience to embrace the fact that this film, itself a highly self-aware take on the cycle, is presented as a cinematic construction rather than a version of triad life that Luke’s daughter may consider “closer to real life.”

The first credit on screen, even before the actual film starts, in The Mobfathers is the logo for the production company HK Film. In an era dominated by co-productions with the People’s Republic of China, this announces a work that is almost defiantly from Hong Kong, and in doing so suggests a feeling that this Hong Kong product is different, almost independent from those co-productions. This is followed by the titles “CHAPMAN TO presents” “a HK FILM PRODUCTION LIMITED production.” Chapman To, the lead performer in the film, had established himself as a bankable star in a series of outrageous “local” comedies that often used self-reflexive cinematic references as part of their humour, such as Vulgaria (Pang Ho-cheung, 2012) and SDU: Sex Duties Unit (Gary Mak, 2013). These films seemed, due to their risqué sexual content and plethora of local Hong Kong references, designed to be too much for Mainland China’s censors to approve. Following his vocal support for the 2014 Umbrella Movement protesters, Quin and Wong reported in The New York Times that To had been placed on a blacklist of performers who were not welcome in the Mainland China film industry.

The combination of the assertion that this is a HK Film production and the appearance of Chapman To’s name, in the context of the cultural politics of Hong Kong, suggests that the film may certainly have been read by local audiences as commenting on recent events. Reviews of The Mobfathers at the time of its release were also conscious of what they saw as the politically nostalgic tone of the film. The Hollywood Reporter led their review by Elizabeth Kerr with a headline that referred to the film as “a fast-paced triad thriller that recalls the glory days of Hong Kong crime flicks,” before going on to state that the film’s director Herman Yau “doubles down on the political commentary by casting two actors allegedly blacklisted in China in starring roles and unleashing the kind of Category III bloody mayhem that made him famous.”

The political commentary that Kerr observes in the film appears very early on. Near the beginning of the film To’s Chuck Lam, a minor triad gang leader, is sent to prison. Whilst sitting in the exercise yard, he is brought a newspaper by a fellow inmate and gang member. As he reads it, there is a significant exchange that highlights the film’s desire for its politics to be picked up on by audiences early on. He warns his fellow triad inmates: “Remember, Triads or not, you must pay attention to what’s happening around you, to keep up with the times.” The paper deliverer replies, “But I hate politics,” to which Chuck counters, “You do? Nowadays buying groceries in the wet market involves politics, too.” For Chuck, even the everyday life of Hong Kong has become political. Here we can see an approach by the filmmakers that places political comment within the context of well-established genre codes and conventions familiar to cinema-goers. As the film progresses, its self-reflexive strategies begin to emerge through its use of the well-established codes and conventions of the triad film and clear references to other films that had adopted the form to make political comment.

Given the early politicisation of its gangsters’ life in Hong Kong in The Mobfathers, it is unsurprising that Herman Yau, and his regular screenwriter Erica Li, go on to pepper the rest of the film with characters, plot developments and narrative twists that whilst they are familiar staples of the Hong Kong triad film can also be clearly read as commenting on the political situation of Hong Kong and its inhabitants almost twenty years after its reunification with The People’s Republic of China. Central to this is the focus on the theme of elections, something that instantly brings to mind the plot of Johnnie To’s Election (2005) and Election II (2006), films explicitly referenced in The Mobfathers. It is here that The Mobfathers, while being at its most explicitly self-reflexive, reminding the audience of its status as a piece of genre cinema, also operates at its most allegorical, drawing on audience’s potential to “read” the triad election politically, having been introduced to such a strategy by To’s films. After the 1997 handover, the election of Hong Kong’s Chief executive had become a point of much controversy. The post of Chief Executive is selected by a small electoral college of 1,200 and has to be approved by the Central People’s Government (of the People’s Republic of China). This has meant that many in Hong Kong have labelled the Chief Executive as a Beijing-approved official rather than a real representative elected through universal suffrage. The desire for universal suffrage and the ability to elect their government’s leader directly has been at the core of many of the protests that have taken place in Hong Kong in recent years.

The idea of democracy within the film’s Jing Hing triad is where The Mobfathers deals with this issue head-on. From early on the audience is presented with an aging “central committee” who head up the triad and select who can be a candidate to take over as its titular Dragon Head. In his review for ScreenDaily, James Marsh (2019) picks up on the allegorical aspects of Wong’s character. Representing a critique of the Beijing government, he argues that “Wong portrays the figurehead as frail, disease-ridden and woefully out-of-touch.” A key early scene sees Anthony Wong’s Godfather call a meeting of the triad’s central committee of four where they go through the possible candidates for Dragon Head. The nominal head of the gang must, for them, represent continuity and always and unquestioningly undertake their bidding. The committee’s first choice is the insider Coke, who is close to them and whom they see as a continuity candidate. Once again, The process of the election of a new leader is not only central to the plot of The Mobfathers,but also to the way in which the film appeals to local audiences using their familiarity with the codes and conventions of a well-established and familiar crime genre. In addition, the evocation of a significant film genre from Hong Kong’s cinematic past can be read as an articulation of the issues and challenges that face the idea of democracy in the territory at the time of production.

The question of democracy really takes central stage in the drama 40 minutes into the film, following the appearance of the film’s title credit, The Mobfathers, suggesting that this is when the real story begins. In the lead up to the election, Chuck re-establishes himself following his incarceration, then expands the territory of his minor triad gang “metal” as well as strategically forging alliances with other gangs within the Jing Hing triad. Following this, we see Chuck telling the Godfather that he wants to stand for the Jing Hing leadership. The Godfather explains the situation as he sees it to Chuck; he may want to stand for Dragon Head, but only the Godfather and the three other members of the central committee of elders can actually decide on who can stand stating, “It’s not up to you to say who’s in or out. We aren’t dealing with a club membership.”

It is during the election process, which comes down to Chuck and another young gang leader Wulf, that the film makes its most telling points that relate most clearly to Hong Kong’s election process. As the procedure is in progress, each gang in the triad gets to vote, Chuck interrupts proceedings and states that the process is problematic. He states, “Why are only nine men eligible to vote when it comes to picking a Dragon head? […] If we vote, every one of us should be eligible.” He challenges the Godfather to adapt the election process for the time, asking “Why not one-man-one-vote,” which is supported by the grass roots members of the gang who chant “I do” in response to Chuck’s question “Do you want the right to vote?”

This sequence is followed by a number of scenes that show Chuck’s family attacked, first in a restaurant where his wife is killed with a machete, and then in a hospital where his son dies as a result of an asthma attack brought on by the altercation. Again operating allegorically, clearly the suggestion here is that, as in the film, the call for universal suffrage in Hong Kong will not be taken lying down by those in power and that they will potentially respond violently to maintain their control. The Godfather also uses his connections to law enforcement officials, who he asserts owe stability to the Jing Hing saying that due to them “everything is in good order, harmonious and stable,” to ensure that when Chuck and Wulf clash they are both eliminated and he continues in control of the triad. The final words of the film, from the now dead Chuck, remind us that the Godfather was wasting away from the inside and that he died months later. The level of interfilmic references present in The Mobfathers invites audiences to see the film as being more than simply a rehash of familiar characters, and genre codes and conventions. If this invitation is accepted, this in turn suggests we can read the character of the Godfather as representing those in power in Mainland China. The film’s ending in this instance becomes optimistic, suggesting that the death of Chuck and his family is ultimately not for nothing. This is an ending that once again uses the familiar Hong Kong genre of the triad film as a way of inviting the audience to also see it as commenting on the contemporary politics of Hong Kong.

Rigor Mortis (2013) and The Sleep Curse (2017): Nostalgia for Hong Kong Horror

Another genre that has had very particular manifestations within the context of Hong Kong cinema is the horror film. In the 1970s, the genre offered the opportunity for more violent and sexually explicit material to be included in low budget studio films such as Killer Snakes (Kuei Chih-Hung, 1974), which utilised real Hong Kong locations. By the turn of the decade, ghosts and the supernatural provided for moments of explicit content in films such as Hex (Kuei Chih-Hung, 1980), Hex vs. Witchcraft (Kuei Chih-Hung, 1980) and The Boxer’s Omen (Kuei Chih-Hung, 1983). These films drew on a variety of regional folklore and offered spectacles that caught audiences’ imagination.

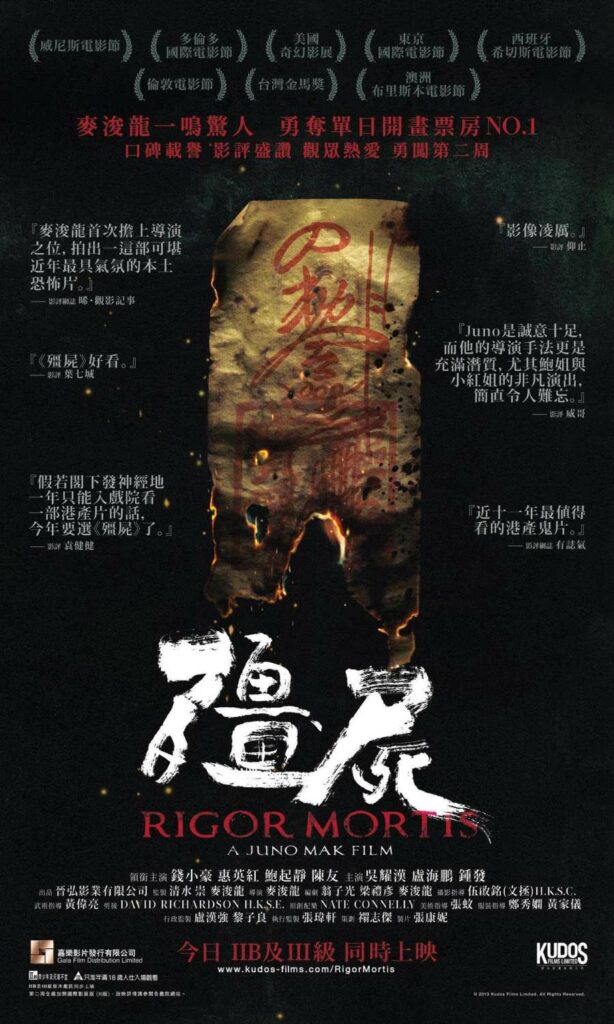

Figure 5. Poster for Rigor Mortis evokes the conventions of the Chinese vampire story

Throughout the 1980s and into the early 1990s, a decade that was a high point in terms of the number of films made in Hong Kong, horror was successful enough at the local box-office and internationally to ensure that a large number of films within the genre were produced. Some of these became landmark films of the era and helped establish popular performers as international stars. For example, A Chinese Ghost Story (Ching Siu-tung, 1987) contributed significantly to the local and international stardom of Leslie Cheung, as well as establishing once again the popularity of films that drew on regional Chinese folklore. Exploring more recent examples of Hong Kong horror films, Vivian Lee has argued that

Cinematic horror in the cultural imagination of post-1997 Hong Kong gains in complexity as the film industry is increasingly integrated into the regulatory regime in Mainland China, which still harbours exceptional caution towards ideologically suspect films, which naturally include those that promote “superstition” through the supernatural. (204)

She also states that recent Hong Kong horror films are of interest because of the fact that in her opinion a “determining factor of their popularity is perhaps the politics implicit in the production and consumption of these ‘local’ horror films: they signal an about-turn from the co-production paradigm” (206). In addition, these horror films also draw on a “cultural memory” in local audiences, in particular of the history of Hong Kong cinema, its performers, visual style, and production cycles, something that can be utilised through inter-filmic references as in the case of Rigor Mortis, but which may also involve extratextual knowledge as in the case of The Sleep Curse.

Rigor Mortis, a 2013 horror film directed by Juno Mak, a well-known singer and actor, is a film that evokes this moment in the history of Hong Kong cinema. Writing about the film, Marco Wan has indicated how fruitfully the film may be read in relation to the political moment of its release in October 2013; his argument acknowledges the importance of nostalgia to the film, in particular its evocation of the popular light-hearted horror vampire films of the 1980s. Like the makers of Gallants, Rigor Mortis conjures up memories of a Hong Kong “golden age” of high production and wide international distribution. It also offers a high level of self-reflexivity through the fact that one of the lead actors, Chin Siu-Ho, is playing a fictional version of himself. This “fictional” Chin Siu-Ho is a former teen film star, now seeking a quiet spot where he can reflect on his life (and ultimately attempt suicide). He moves into an apartment block that is afflicted by high levels of supernatural activity and surrounds himself with costumes and other ephemera from his filmmaking past. Alongside Chin, Mak inhabits his film with a number of actors Hong Kong audiences would instantly link to the film industry’s past, and in particular to the vampire story. In addition to Chin Siu-Ho, the production cast a number of actors who appeared in one or more of the Mr Vampire series of films that were local hits in the 1980s, most notably, Anthony Chan, who had played a Taoist priest in Mr Vampire (1985) and Mr Vampire Saga (1988); Fat Chung, Richard Ng and Billy Lau.

The Hong Kong vampire film is a local sub-genre that in Juno Mak’s reimagined form had little chance of appearing in Mainland cinemas due to its representation of the supernatural. The act of creating such a film can in some ways be read as a political move on behalf of the director and his team. Certainly, the inclusion of traditional ghosts and spirits along with reanimation of the dead through ancient spells works in this regard and is clearly linked directly to Hong Kong’s cinematic history.

One of the lesser noted, though highly relevant to local politics, aspects of Rigor Mortis is its focus on older characters. It presents its older characters as somehow left behind by the changes in Hong Kong. For example, the on-going development and gentrification of areas of the city, which moves out established communities, is reflected in the stylised mise-en-scène Mak employs to create his characters’ living environment. The public housing block in which the action takes place seems forgotten, rundown and marginalised. This works to create a sense of dread as the new occupant arrives, the character is a former actor now also forgotten and who finds himself on the social margins like those who already live there. As he settles in, he finds out that other occupants of the apartments have mental health problems. Together, they represent the forgotten, the marginalised and in many ways the unsupported in a Hong Kong society driven by international finance and a desire for wealth. Significantly, these old folks are also the carriers of Hong Kong’s cultural memory, a resource that may be lost as they end their days.

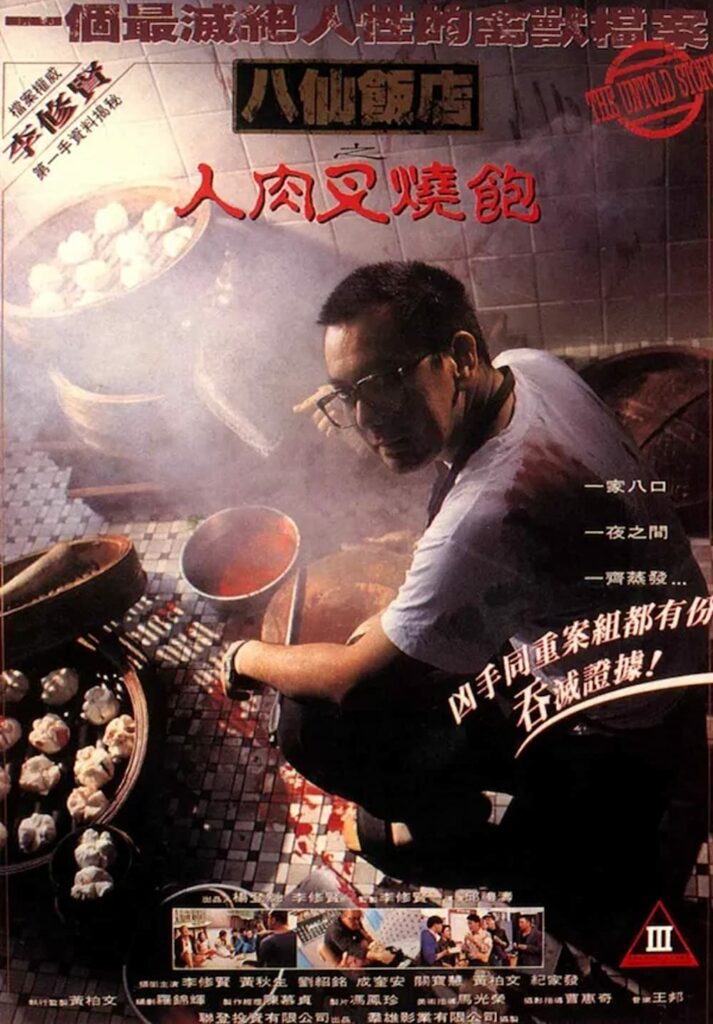

If Rigor Mortis is a film that can be read as political through its self-reflexive references to Hong Kong’s cinematic past, such as casting Chin Siu-ho and evoking the mise-en-scène of the 1980s cycle of ghost story films, The Sleep Curse, released in Hong Kong in May 2017, is another film whose politics also draws on a series of inter- and extra-textual references that are based on the histories of Hong Kong cinema and its creative personnel. Key to this set of references is the creative collaboration between director Herman Yau and actor Anthony Wong. Before The Sleep Curse, Yau and Wong had worked on a series of socially conscious horror films that combined strikingly gory imagery with a liberal engagement with social and political issues. The best-known results of that collaboration are The Untold Story (Herman Yau, 1993), Taxi Hunter (Herman Yau, 1993) and Ebola Syndrome (Herman Yau, 1996). Together, the pair became synonymous with a particular type of violent horror film that globally became closely associated with the Hong Kong cinema of the period and is often referred to as Category III. This label refers to the Hong Kong censorship category introduced in 1988 through the “Movie Screening Ordinance Cap.392;” according to the Hong Kong government, it concerns those films that are “Approved for Exhibition Only to Persons who have Attained the Age of 18 Years.” The combination of Yau and Wong therefore had significant meaning for Hong Kong filmgoers.

The 2017 release The Sleep Curse saw the actor and director collaborating once again. The marketing and reception of the film highlighted the re-teaming as a key element of the film. For example, in The Hollywood Reporter Clarence Tsui noted that:

Fans of The Untold Story or The Ebola Syndrome, rejoice. Herman Yau, the maverick mind behind those two Hong Kong cult classics from the 1990s, has returned to the realm of ultra-gory, exploitative entertainment with The Sleep Curse… The Sleep Curse looks more like a stunt in itself, starting from Yau’s reunion with actor Anthony Wong, who attained his A-list status through his turns as pathological killers in both The Untold Story and The Ebola Syndrome.

Given this history, Hong Kong audiences would very likely bring a clear set of expectations to the film, particularly its violent images. The story is set in 1940 during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong and 1990 when the son of a character cursed in the wartime sequences finds he is suffering from the same malediction. Both time-settings, the occupation period and the 1990s, are associated with Hong Kong before the reunification with China; the scenes set in the 1990s, and the violent imagery, also clearly evoke the director and actor’s work of that period.

Figures 7 and 8. Poster art for The Sleep Curse seems to evoke that of an earlier violent collaboration between actor Anthony Wong and director Herman Yau, The Untold Story.

The politics of nostalgia can clearly be found once again in the casting of The Sleep Curse. However, here it is in a manner that is slightly different from the ideas of an older Hong Kong evoked by the casting of films like Gallants and Rigor Mortis. As noted earlier, Anthony Wong had reportedly had issues with gaining work in productions with links to the People’s Republic of China because of his alleged support for the 2014 Umbrella Movement protests. This was noted by The South China Morning Post when reporting from the 2019 Udine Far East Film Festival in Italy, where Wong was a guest and asked directly about this issue. James Marsh noted that “his vocal support of the 2014 ‘umbrella movement’ pro-democracy sit-ins in Hong Kong and criticism of China’s Communist Party has seen him blacklisted, with job offers drying up, especially offers from China.” Local audiences would therefore be well aware of Wong’s reputation, and would potentially read his appearance in the film as having a political frisson.

In addition to Wong’s presence, the violence within the film may also be interpreted as offering another political response to the cultural politics of Hong Kong at the end of the 2010s. The Category III style violence would certainly make sure that The Sleep Curse would be unlikely to be able to be released in Mainland China ever. Yau himself, at a Q&A session after a screening of the film at the HOME arts centre in Manchester, suggested that its construction, in particular the casting of Anthony Wong and the inclusion of explicit images of violence, might remind people that Hong Kong cinema is different, and has a particular history separate from that of Mainland China, and that the horror film has played a key role in Hong Kong film history. It seems to me that in making this point Yau was referring to his earlier collaborations with Wong such as The Untold Story, Taxi Hunter and Ebola Syndrome, films whose violent and excessive, bloody imagery has come to be seen as emblematic of the distinctiveness of Hong Kong’s 1990s Category III films. The Sleep Curse can therefore be read as a fascinating example of how a Hong Kong horror film can use the idea of reflexivity in terms of the territory’s cinema history to make a coded statement about the contemporary industry and its relationship with that of the People’s Republic of China.

Whilst a number of influential writers, such as Jameson (1998), have considered the presence of nostalgia as a potentially negative component of contemporary cinema, when one looks in detail at the specific manifestation of a cinematic nostalgia in recent Hong Kong films it becomes clear that there is an available reading that helps re-calibrate this idea to embrace a political reading of these works that asserts the continued difference of Hong Kong as both a real and an imagined cinematic space in the face of its rapid assimilation into the wider identity of the PRC. The gangster and horror films discussed here therefore offer a particularly Hong Kong take on the self-reflexive tendencies in contemporary cinema. In their references to Hong Kong’s very particular cinematic past, its popular film cycles, performers and its visual style, films such as Gallants, Rigor Mortis, The Mobfathers and The Sleep Curse can certainly be read politically at a time when some people in the territory are actively attempting to assert its socio-economic and cultural difference against what they see as its impending integration into Mainland China. This is an act that will, from their perspective, erase Hong Kong’s own particular social, political and legal structures as well as its cultural identity. In a territory where film has for so long been such an important part of local identity, I would argue that the films and filmmakers I have discussed here are using self-reflexive references to a filmmaking past to assert that Hong Kong cinema, and by extension Hong Kong itself, has the potential to continue to be a distinctive, different and in many ways unique entity in its own right.

Andy Willis

Works Cited

Abbas, Ackbar. Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance. University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Bordwell, David. Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. Harvard University Press, 2000.

Cheung, Ruby. New Hong Kong Cinema: Transitions to Becoming Chinese in 21st-Century East Asia. Berghahn Books, 2015.

Chu, Yiu-Wai. Lost in Transition: Hong Kong Culture in the Age of China. SUNY Press, 2013.

Ge, Celine. “It’s fade out for Hong Kong’s film industry as China moves into the spotlight”. South China Morning Post, 28thJuly, 2017. https://www.scmp.com/business/article/2104540/its-fade-out-hong-kongs-film-industry-china-moves-spotlight

Jameson, Fredric. The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings on the Postmodern 1983-1998. Verso Books, 1998.

Kerr, Elizabeth.“The Mobfathers: Filmart/HKIFF Review”. The Hollywood Reporter, March 23, 2016. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/mobfathers-filmart-hkiff-review-877615

Lee, Vivian. “Ghostly Returns: The Politics of Horror in Hong Kong Cinema”. Hong Kong Horror Cinema, edited by Gary Bettinson, Daniel Martin. Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

Marsh, James. “The Mobfathers: HKIFF Review”. ScreenDaily, March 29, 2016. https://www.screendaily.com/reviews/the-mobfathers-hkiff-review/5101972.article

Marsh, James. “Of course I’m scared’: outspoken actor Anthony Wong on his Hong Kong future, and acclaim for Still Human”. South China Morning Post, May 2019. https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/entertainment/article/3010096/course-im-scared-outspoken-actor-anthony-wong-his-hong-kong

Quin, Amy and Wong, Alan. “Stars Backing Hong Kong Protests Pay Price on Mainland”. The New York Times, 24 October, 2014.https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/25/world/asia/hong-kong-stars-face-mainland-backlash-over-support-for-protests.html

Shackleton, Liz. “Filmart: how Hong Kong film industry is adapting to challenging times”. ScreenDaily 14 March, 2019. https://www.screendaily.com/features/filmart-how-hong-kong-film-industry-is-adapting-to-challenging-times/5137634.article

Teh, Yvonne. “Film review: Dot 2 Dot is a touching love letter to Hong Kong”. South China Morning Post, October 2014. https://www.scmp.com/magazines/48hrs/article/1626675/film-review-dot-2-dot-touching-love-letter-hong-kong

Teo, Stephen. Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions. British Film Institute, 1997.

Tsui, Clarence. “The Sleep Curse”. The Hollywood Reporter, 21 March, 2017. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/sleep-curse-sut-min-film-review-hong-kong-2017-994405

Wan, Marco. “The language of Film and the Representation of Legal Subjectivity in Juno Mak’s Rigor Mortis”. Meaning and Power in the Language of Law, edited by Janny HC Leung and Alan Durant (eds) Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp 118-134.