David Cronenberg has rarely been regarded as an overtly religious filmmaker. Raised in a secular Jewish environment, he has consistently rejected organised forms of belief. In a 2013 interview, he described himself as “an atheist who finds religion claustrophobic and oppressive,” adding that “atheism is an acceptance of what is real.” (1) In 2005, however, reflecting on A History of Violence (2005), Cronenberg articulated a more dialectical position, describing himself not as an atheist but as a materialist — one for whom existence is defined by the physical and the tangible rather than the transcendent. (2)

Cronenberg’s cinema has always been grounded in this uncompromising materialism. Across his oeuvre, bodies mutate, machines penetrate flesh, and mortality asserts itself without the promise of redemption. He has consistently refused metaphysical consolation, affirming instead that biology and technology delineate the boundaries of human experience. Yet, paradoxically, his films often stage encounters that verge on the theological — moments when flesh, mortality, and community provoke questions of meaning that seem to exceed the merely material.

The Shrouds (2024) marks a culmination of this trajectory. Paradoxically, it is Cronenberg’s most religious — or perhaps more precisely, most post-secular — film in his own way. It does not affirm doctrine; rather, it confronts death as the ultimate horizon of both capitalism and faith. The premise is deceptively simple yet profoundly unsettling. Karsh (Vincent Cassel), a grieving widower and self-professed “non-observant atheist,” invents a funerary technology that allows clients to monitor, in real time, the decomposition of their deceased loved ones. Marketed as therapeutic, this system promises to close the gap between presence and absence, as if technology could mediate intimacy with the dead. Yet what appears as connection is revealed to be consumption: grief becomes a service, mourning is privatised, and physical decomposition is rendered as spectacle. Cronenberg has acknowledged that the project arose directly from his own experience of loss — his wife, Carolyn Zeifman, died in 2017 — giving the film an unmistakably personal dimension. (3)

To interpret this vision, Marxist theory provides a crucial critical framework. Karl Marx argued that under capitalism, social relations are transformed into relations between things: commodities acquire an apparent intrinsic value that conceals the labour that produced them. (4) In The Shrouds, grief itself becomes fetishised as commodity — a technological mediation that masks alienation. Achille Mbembe’s concept of necropolitics elucidates how colonial sovereignty operates through the power to decide who may live and who must die. (5) Yet in Cronenberg’s late vision, sovereignty over life and death no longer resides with the colonial state but shifts toward capital itself, which now governs even the afterlife of the corpse. This condition aligns with Subhabrata Bobby Banerjee’s concept of necrocapitalism — an economic system that transforms death and bodily disposability into sources of profit. (6)

The film, however, is not merely an allegory of commodification. By confronting viewers with the visceral spectacle of decomposition, Cronenberg foregrounds the resistant force of matter itself. The corpse resists abstraction, disrupting the fantasy of mastery that Karsh’s device promises. This resistant materiality recalls Georges Bataille’s reflections on excess and expenditure. (7) If capital seeks to translate every experience into financial value, the decaying body testifies to what cannot be absorbed — what refuses incorporation into the smooth circuits of exchange.

This resistance also opens a theological dimension, particularly through the framework of Christian materialism. Christianity, too, affirms the primacy of matter: the Incarnation declares that “the Word became flesh” (John 1:14); the Eucharist effects divine presence through material elements (1 Corinthians 11:24-25); and the resurrection of the body (1 Corinthians 15:42) insists that flesh, even in corruption, is destined for transformation. Theologians such as Kathryn Tanner (2021) have shown that theology, when properly understood, defends the material against capitalism’s abstraction and privatisation. (8)

Reading The Shrouds through both Marxism and Christian materialism reveals a complex confrontation between capital and flesh, abstraction and embodiment, commodification and communion. Both traditions affirm that matter resists reduction, that bodies cannot be collapsed into exchange value, and that death, however terrifying, remains irreducible to commodification. Cronenberg’s film thus occupies a liminal position between disbelief and reverence, where the secular imagination discovers, within its own limits, the endurance of the sacred.

Religion Deferred

David Cronenberg’s relationship with religion has always been marked by both distance and fascination. His early films — Shivers (1975) and Rabid (1977) — depict communities overtaken by contagion, transforming devotion into disease and ecstasy into possession. What appears as corruption becomes liberation: a physical truth breaking through repression. In The Brood (1979), therapy gives monstrous birth to anger. In Videodrome (1983), media technologies evoke cultic devotion. In Crash (1996), wounds acquire ritual intensity. Later works such as Cosmopolis (2012) and Crimes of the Future (2022) transform the body’s dissolution into quasi-theological allegories of capital’s abstraction and art’s creation. Throughout these films, Cronenberg relocates the sacred within the material, translating transcendence into the circuitry of flesh and evoking ritual even as he denies it.

This sustained materialism has often been misread as simple atheism. In fact, Cronenberg’s worldview operates less as denial than as exploration: an inquiry into the possibilities of meaning once transcendence has been refused. His cinema treats the body not as obstacle but as site of revelation. The Shrouds extends this trajectory while redirecting it. Where the earlier films examined the permeability of flesh, this work turns to its disappearance. The death of Karsh’s wife and his inability to mourn her physically mark a crisis within materialism itself. The funeral, once mediating between body and community, is replaced by a technological interface. Mourners no longer gather or touch; they watch, distantly, as cameras transmit decomposition in real time.

As a result, religion in The Shrouds is deferred in two senses. It is first technologically deferred, as ritual yields to mediation and presence dissolves into data. Mourning becomes an endless postponement, suspended between loss and its representation, never resolving into closure or hope. But religion is also conceptually deferred, returning as its own negation. The film’s avowed atheism conceals a post-secular longing — a yearning for meaning within matter itself. Karsh’s invention becomes a parody of faith, an attempt to render the invisible visible, to witness what ought to remain hidden. The result is not revelation but surveillance.

Cronenberg’s mise-en-scène reinforces this dialectic. The cemetery, once sacred ground, becomes a technological field: screens embedded in stone transmit images of decay, illuminated by cold palettes of grey and blue. Mourning unfolds within a digital purgatory. The screen promises resurrection through image, yet delivers only entropy. This technological deferral of the sacred recalls Paul Virilio’s Aesthetics of Disappearance, in which modernity replaces reality with visibility. (9) For Virilio — whose thinking was grounded in Catholic theology — such a regime of sight is not only epistemological but ultimately theological: visibility without incarnation is illusion. To separate image from flesh is to sever the sacramental bond between the material and the divine. Karsh’s screens enact precisely this separation — a disembodied visibility that annihilates presence, offering revelation without embodiment, faith without touch.

Cronenberg’s cinema has always distrusted transcendence because it is obsessed with seeing. His worlds are populated by instruments that reveal and record — television sets, scanners, cameras, optical lenses, and other technologies of vision. In The Shrouds, this compulsion becomes metaphysical. The desire to see into the grave becomes a form of faith without God, an eschatology of the screen. Yet the film refuses closure. As Karsh stares at the image of his wife’s decay, technological mastery collapses into horror. What was meant to console instead wounds; spectacle implodes into silence. In that rupture, the sacred returns — not as transcendence, but as failure. Technology falters, and the invisible reasserts itself.Religion is thus refused as institution and deferred as belief, yet it reappears as structure and desire. In The Shrouds, this desire takes the form of mourning — the compulsion to make sense of death through gesture and repetition. Cronenberg reveals how capitalism and technology exploit this need, transforming mourning into consumption, yet the longing itself — the yearning to see, to touch, to keep, to remain — is still irreducibly religious. The film inhabits what Charles Taylor calls the immanent frame: a world in which meaning is confined within immanence yet haunted by the persistence of transcendence. Cronenberg’s achievement is to show that the very search for meaning within matter transforms the secular imagination into a religious one. (10)

Mourning as Commodity

At the centre of The Shrouds lies Karsh’s invention: a funerary technology that transforms grief into a marketable product. Marketed as an innovation in the care of the dead, the system allows mourners to subscribe to a service that livestreams the decomposition of their loved ones. In Cronenberg’s clinical world, this apparatus appears not dystopian but therapeutic — a promise of intimacy through visibility, a form of technological healing. Yet this intimacy is an illusion. What appears as care is consumption; what seems like mourning is monetised attention. In Marxist terms, The Shrouds represents the extension of the commodity form into death itself. Marx described the commodity as “a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.” (11) Under capitalism, relations between people become relations between things; objects acquire a false autonomy that conceals the social relations and labour that produced them. Karsh’s funerary technology reproduces this logic with uncanny precision. Grief becomes a commodity fetish — an interface that obscures both the communal process of mourning and the affective labour it entails. The mourners in The Shrouds no longer share rites of lamentation. Instead, they purchase access to privatised grief, replacing ritual with a commercial transaction.

David Harvey’s concept of “spatial fixes” helps clarify the mechanism at work. (12) Capitalism, he argues, sustains accumulation by colonising new spaces and domains of experience. In Cronenberg’s film, this colonisation reaches its final frontier: the grave itself. The cemetery itself becomes a site of production. Cronenberg’s mise-en-scène visualises this transformation through grids of illuminated tombs, screens embedded in headstones, and pathways laced with cables — a digital infrastructure that literalises the circuitry of capital.

The mourners’ relation to the dead mirrors the alienation Marx diagnosed in labour. They encounter death not as experience but as image, consuming it through screens that promise closeness yet deliver distance. What was once an intimate act of relation becomes externalised, outsourced, and resold as subscription. Human affect is commodified and recirculated as product. As Marx argued in his early writings on alienation, human capacities are alienated under capitalism and sold back as commodities. (13) In The Shrouds, this dynamic extends to mourning itself: the very capacity to grieve becomes industrialised.

Lauren Berlant’s notion of “cruel optimism” refines this diagnosis. (14) The mourners’ attachment to Karsh’s device rests on a fantasy of healing that perpetuates their loss. They believe surveillance will bring comfort, yet the very mechanism of comfort reproduces alienation. The viewer remains suspended between presence and absence, unable to move through mourning because mourning has been reconfigured as a consumable loop. Consolation becomes repetition — a product designed to perpetuate its own necessity.

This dynamic finds expression in the film’s treatment of Becca’s haunting doubleness. Her sister Terry and the virtual assistant Hunny — both played by Diane Kruger — extend Becca’s presence through uncanny substitution. Terry revives her memory as physical echo; Hunny translates that echo into algorithmic simulation. Between them, Karsh encounters Becca as both flesh and data, desire and code. This doubling collapses the boundary between grief and reproduction, revealing Karsh’s devotion as technological optimism sustained by illusion. His dreams of an increasingly mutilated Becca, intercut with scenes of Terry and Hunny, blur mourning into fantasy. Cronenberg transforms this proliferation of images into a visual theology of repetition: consolation that reopens the wound. Becca reappears everywhere except where she is gone.

Mourning as consumption is an example of what Guy Debord called “the spectacle”: a social relation mediated by images, in which representation supplants lived experience. (15) In The Shrouds, mourning becomes spectacle itself — an image replacing ritual, a mediated substitute for presence. The dead are no longer remembered but streamed; grief becomes a genre of consumption. What was once communal rite becomes privatised spectatorship. In place of funerals, interfaces; in place of solidarity, isolation. Cronenberg’s detached aesthetic intensifies this alienation. Refusing the sentimental tropes of loss, The Shrouds adopts a tone of clinical restraint. Its pacing is slow, its performances contained, its imagery austere. Emotion is flattened into interface, intimacy reduced to transaction. This stylistic coolness is not mere affectation but functions as a formal analogue of the film’s critique: the very texture of its detachment mirrors the commodified mourning it portrays.In the contemporary landscape of algorithmic intimacy and digital memorialisation, The Shrouds reads less as speculative science fiction than as a cultural diagnosis. Livestreamed funerals, online obituaries, and virtual cemeteries already turn grief into public, monetised visibility. Cronenberg amplifies this reality into allegory, exposing what Marx called the “theological niceties” of the commodity form — the secular continuation of religious desire through capitalist structures. The promise of technological transcendence — of overcoming death through data — echoes the Christian narrative of resurrection, but in degraded form. Karsh’s devotion mimics faith’s longing for communion, yet his solution enacts its parody: not the transfiguration of flesh, but its endless decomposition in high definition.

The Resistant Corpse

If The Shrouds depicts the commodification of mourning as capitalism’s final frontier, it also insists that death resists complete assimilation. However advanced Karsh’s technology may be, the corpse defies abstraction. What begins as an attempt to contain death through visibility ends as a confrontation with matter’s irreducible autonomy. Cronenberg transforms decomposition into a quiet rebellion, exposing the limits of both capital and technology.

To watch a body decay is to encounter something that cannot be fully consumed. The film dwells on images of decay, but in contrast to the visceral excess of Cronenberg’s early works, these moments are composed with stillness and contemplation. Flesh collapses gradually; colour drains; silence dominates. The effect is not sensational but meditative, forcing spectators into a bodily recognition of finitude. This aesthetic stillness converts disgust into reflection, making the persistence of matter more palpable.

“The corpse, seen without God and outside of science, is the utmost of abjection,” writes Julia Kristeva, for it disrupts the boundaries between self and world, life and death. (16) The Shrouds makes this disruption visible. The decomposing body refuses containment within any symbolic or technological order. Karsh’s system seeks to domesticate death through vision, but the closer he looks, the less control he possesses. The abject exposes the futility of mastery: the body’s disintegration undoes both representation and possession.

This refusal recalls Bataille’s notion of expenditure — the excess that escapes the logic of utility and profit. (17) Death and decay, for him, belong to an “accursed share” of existence: waste without return, energy that resists recuperation by economic systems. In The Shrouds, decomposition embodies precisely this excess. The networked apparatus that transforms graves into screens cannot convert decay into value or meaning. What Karsh conceives as closure collapses into entropy. Cronenberg’s restrained aesthetic reinforces this tension. His static, layered compositions reject the velocity characteristic of both popular cinema and capital, each driven by perpetual circulation and replacement. Every frame becomes a meditation on endurance — an insistence on the material duration of the body and an ethics of attention that resists spectacle.

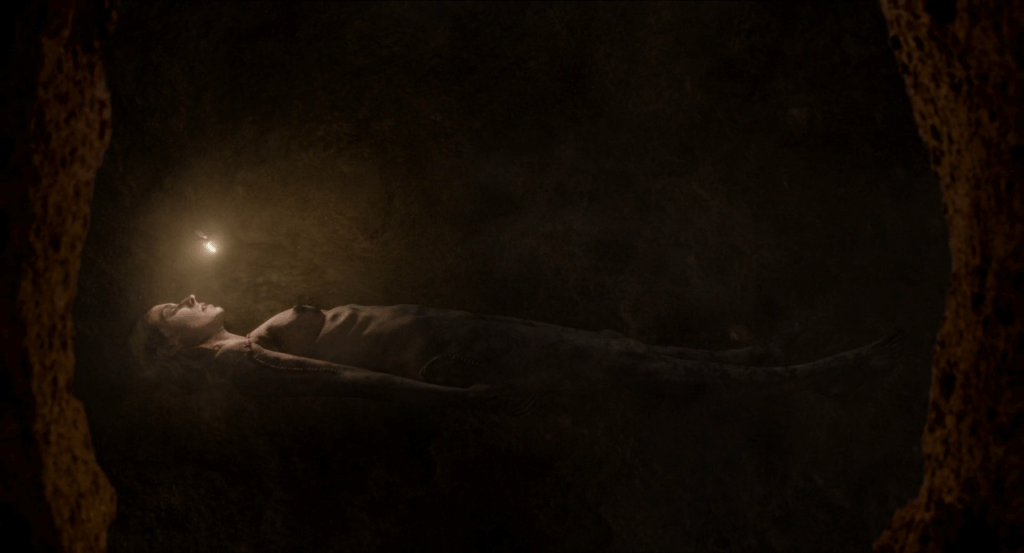

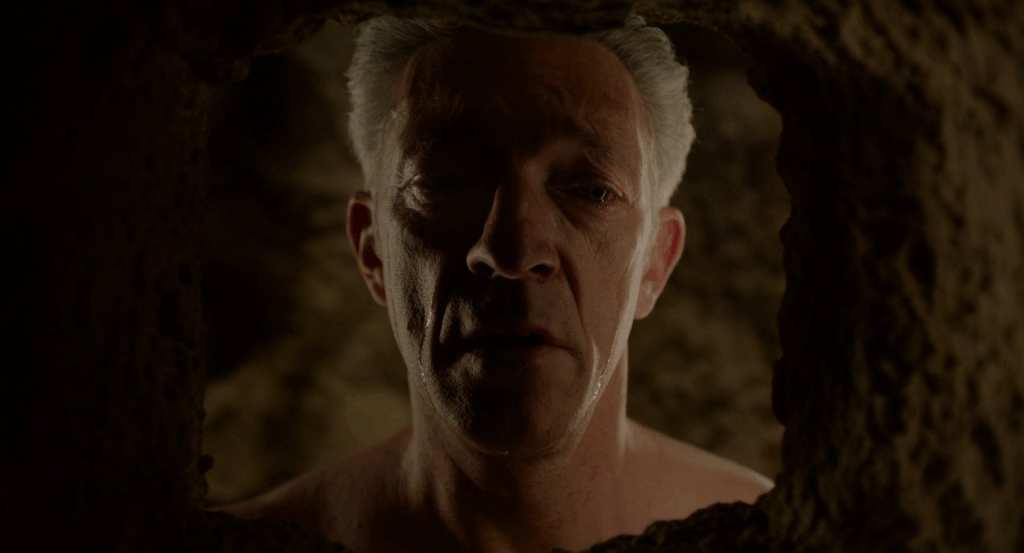

The film’s dream sequences extend this meditation into the unconscious, where suspension becomes both formal and emotional. The opening sequence is emblematic. Becca appears not as revenant but as a lifeless body suspended beneath the earth. Her skin emits a faint glow, animated by a hovering insect that circles her like a flickering light. From an adjoining chamber, Karsh observes, alive yet hollowed by grief. His cry, half anguish and half invocation, reverberates through the subterranean space. The image implodes into waking life: the camera plunges into the darkness of his open mouth, emerging into the glare of a dental lamp. A gloved hand enters the frame to probe his teeth. “Grief is rotting your teeth,” the dentist remarks — a line that fuses psychic and bodily decay.

This early scene establishes the film’s governing rhythm: the oscillation between mourning and matter, intimacy and intrusion, the sacred and the clinical, culminating in the tension between the spiritual and the material. Every image becomes a meditation on transformation — on the slow passage from presence to absence. The disintegration of the body mirrors cinema’s own ontology: movement as vanishing. As Vivian Sobchack argues, film is an embodied medium that touches the spectator through sensation. (18) Cronenberg mobilises this capacity with precision, allowing the viewer to feel decay not as horror but as recognition — the recognition of mortality shared by image and body alike.

Terry Eagleton offers a helpful theological frame for this materialism. Following Aristotle and Aquinas, he observes that a corpse is not truly a body but only its residue. (19) The living body, in this view, is not an inert substance but the expressive form of the person; once life departs, the body ceases to exist as such. The corpse, then, is not the person in another mode but the negation of presence — the trace of what no longer lives. Cronenberg confronts the spectator with this truth: what we call “the body” exists only in motion, relation, and flux. Once immobilised, it becomes a sign of its own disappearance. The Shrouds makes us witness that disappearance — the slow undoing of form that is at once terrifying and strangely serene. In this undoing, Cronenberg discovers a paradoxical persistence. Matter, even in dissolution, refuses to vanish completely. Decay becomes not mere end but transformation: a passage through which life’s trace continues to reverberate. Against the abstraction of necrocapitalism, The Shrouds asserts that material existence cannot be entirely commodified. Its resistant corpse stands as a remnant of the real — a sanctified remainder that reclaims the body’s dignity precisely through its refusal to serve.

The Religious as Other

In The Shrouds, David Cronenberg exposes both the commodification of mourning and the resistant vitality of the corpse, yet he also reintroduces the question of the sacred — not as belief, but as that which persists beyond commodification. Having long rejected organised religion, Cronenberg finds himself haunted by what theology names and capital cannot contain: the irreducibility of matter, the persistence of flesh, and the communal necessity of mourning. His late work, especially The Shrouds, marks a distinct post-secular turn: a meditation on what remains of faith when transcendence is denied but the desire for meaning endures.

The religious in The Shrouds thus emerges not as doctrine but as otherness — the dimension of material existence that cannot be mastered or reduced. In this sense, Cronenberg’s vision aligns with John Milbank’s reflections on materialism and transcendence. (20) He argues that a purely immanent materialism collapses into banality, while theology alone preserves the depth and mystery of matter. For him, materiality itself gestures beyond itself, testifying to a plenitude that secular reason cannot exhaust. The Shrouds translates this paradox cinematically: its images of decomposition reveal the stubborn vitality of flesh, a persistence that gestures toward the sacred even in the absence of belief.

Karsh’s funerary technology — designed to broadcast the decomposition of the dead — imitates religion while hollowing it out. It offers nearness without communion, ritual without community. In place of collective mourning, Cronenberg presents isolation before a glowing screen. The mise-en-scène evokes the architecture of worship — rows of luminous graves, glacial blue light, a camera that lingers as if in prayer — yet this is liturgy emptied of transcendence. In this hollowing, Cronenberg stages the mutation of the sacred under late capitalism: the communal act of remembrance becomes a private subscription. His world is devotional without divinity and reflects an age in which technology reproduces the structures of religion while stripping them of spiritual significance. Karsh’s gaze upon the decaying body of his wife becomes a new form of prayer — intimate, obsessive, and unanswered.

Christian theology provides a provocative counterpoint. The doctrine of the Incarnation — that “the Word became flesh” (John 1:14) — asserts the sanctity of matter by locating divinity within it. Cronenberg’s cinema has long been fascinated by flesh as medium and message, but in The Shrouds this fascination takes a darker turn. Incarnation is reversed: not divinity entering matter, but matter collapsing under the absence of divinity. Karsh’s attempt to render death visible parodies revelation; his technology seeks to redeem flesh through visibility, yet exposes only its decay. This is incarnation without grace — a material creed of flesh without hope.

The resurrection is similarly inverted. Christian theology proclaims the transformation of matter — that “what is sown in corruption will be raised in incorruption” (1 Corinthians 15:42). In The Shrouds, the dead return not in renewed life but in digital replay. Karsh’s device resurrects nothing; it merely prolongs death’s visibility. Yet, in depicting this failure, Cronenberg recalls what genuine resurrection would entail: not endless seeing, but release; not mastery, but communion.

When the system collapses in the film’s final act, the screens go dark and silence descends as Karsh and Terry walk among the graves. What remains is absence — and within that absence, a faint trace of grace. Cronenberg still refuses transcendence, yet he allows space for stillness: a moment in which the living confront loss without the mediation that once buffered it. This silence becomes the film’s most profoundly religious gesture — not revelation, but relinquishment.

In this way, The Shrouds articulates a form of material spirituality, a reverence for what persists within the confines of immanence once transcendence has been refused. The corpse, the screen, and the spectator each participate in a new kind of liturgy: one stripped of metaphysics yet charged with longing. If capital turns mourning into consumption, Cronenberg transforms consumption into contemplation. He discovers, within the abject, the residue of the sacred.Thus, The Shrouds is not anti-religious but dialectically religious. It enacts the exhaustion of transcendence and the persistence of devotion within immanence. The sacred returns not as faith but as matter’s resistance — the sanctified endurance of flesh. In making death visible and unbearable, Cronenberg reveals that belief survives even in its negation, that the material world, left to itself, still vibrates with the echo of the divine.

Conclusion: Persistence of Flesh

David Cronenberg’s The Shrouds transforms death into a mirror reflecting both capitalism and faith. Its central invention — a funerary technology that allows mourners to witness the slow decomposition of their loved ones — embodies capital’s drive to commodify even grief. Yet the film’s horror lies not in death itself, but in the attempt to domesticate it. Cronenberg shows that matter, even in decay, resists the abstractions of profit and control. The corpse exposes the limit of commodification: flesh cannot be stabilised into product or spectacle without remainder.

This resistance renders The Shrouds simultaneously materialist and theological. Through a Marxist lens, the film exposes the fetishism of mourning as commodity; through a theological lens, it reasserts the sanctity of matter. Incarnation and resurrection, understood as affirmations of embodiment, counter Karsh’s technological parody. Where capitalism isolates, theology gathers; where capital abstracts, theology affirms; where the screen simulates presence, faith insists upon the body’s enduring reality.

One of the film’s most striking moments arises when Karsh, recalling his wife’s Jewish heritage, meditates on the body’s gradual dissolution after death:

For the Jews, the body must slowly disintegrate so that the soul, which is obsessed with that body, which loves that body, which hovers over that body, and is reluctant to leave it, which has seen the world only through the eyes of that body, has time to gradually let go of that body, say goodbye to it, and then ascend to Heaven.

This passage articulates a distinctly Jewish metaphysics of flesh, though it does so also through the Christianised language of ascension to heaven. In contrast to the capitalist logic of instant display, Jewish ritual enacts patience and humility before the body’s lingering presence. In The Shrouds, this perspective reinterprets decay as something worthy of reverence, offering an unwitting midrash on embodiment and release.

The paradox of The Shrouds is that Cronenberg, a filmmaker long associated with secular materialism, has produced his most religious work. Its religiosity does not rest on belief but on attention — on the contemplative regard for mortality as an encounter with what exceeds control. When Karsh’s system collapses and the screens fall dark, death regains its mystery. The sacred returns not as spectacle but as silence. In this stillness, Cronenberg’s materialism acquires a contemplative dimension. Against necrocapitalism, he affirms life-in-death, that is, reclaims death as a locus of embodied truth. Against simulation, he affirms the persistence of matter, that is, the resistance of the physical to its digital abstraction. Through this double affirmation, The Shrouds transforms the spectacle of decomposition into a meditation on the materiality of existence and the spirituality of mourning.

The film thus concludes at the intersection of Marxism and theology. Both traditions, despite their differences, insist that matter resists abstraction and that the body cannot be reduced to function or value. Cronenberg’s vision affirms that flesh — abject, finite, yet irreducible — endures as the medium of truth. The persistence of flesh becomes a form of reluctant sanctity, uniting Judaism’s reverence for the body with Christianity’s hope for its transformation. In The Shrouds, death becomes not the negation of meaning but its final revelation: the point where matter, confronting its own dissolution, discloses the sacred within the real.

Sérgio Dias Branco

- David Cronenberg, “David Cronenberg: ‘I never thought of myself as a prophet’,” interview by Henry Barnes, The Guardian, 12 Sept. 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2013/sep/12/david-cronenberg-suicide-fantastic-exit.

- Cronenberg, “David Cronenberg: A Director Looks at Violent America,” interview by Brad Balfour,

PopEntertainment, 3 Nov. 2005, https://web.archive.org/web/20220528083314/http://www.popentertainment.com/cronenberg.htm. - Cronenberg, “Death Becomes Him: The Shrouds Director David Cronenberg Dips Into the Macabre,” interview by G. Allen Johnson, San Francisco Chronicle, 24 Apr. 2025, https://www.sfchronicle.com/entertainment/article/david-cronenberg-the-shrouds-tesla-20279582.php.

- Karl Marx, Capital: Volume 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1976).

- Achille Mbembe, “Necropolitics,” trans. Libby Meintjes, Public Culture 15, no. 1 (2003): 11-40.

- Subhabrata Bobby Banerjee, “Necrocapitalism,” Organization Studies 29, no. 12 (2008): 1541-63.

- Georges Bataille, The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy, Vol. 1: Consumption, trans.

Robert Hurley (New York: Zone Books, 1988). - Kathryn Tanner, Christianity and the New Spirit of Capitalism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press,

2021). - Paul Virilio, The Aesthetics of Disappearance, trans. Philip Beitchman (New York: Semiotext(e), 1991).

- Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 539-93.

- Marx, Capital: Volume 1, 163.

- David Harvey, The Enigma of Capital and the Crises of Capitalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 50.

- Marx, “Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (1844),” trans. Martin Milligan and “Wage-Labour and Capital (1849),” trans. Friedrich Engels, in Karl Marx’s Writings on Alienation, ed. Marcello Musto (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), 52-58 and 64-66.

- Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

- Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (New York: Zone Books,1995).

- Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 4.

- Bataille, The Accursed Share.

- Vivian Sobchack, Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture (Berkeley: University ofCalifornia Press, 2004).

- Terry Eagleton, Materialism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), 37-38.

- John Milbank, “Materialism and Transcendence,” in Theology and the Political: The New Debate, ed.Creston Davis, John Milbank, and Slavoj Žižek (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 393-426.